The winds of change are blowing: the fisheries sector needs to prepare for some coming storms, and to adapt to a carbon-free future to sustain ocean based life and fishing livelihoods.

Food produced from the oceans provides an essential source of nutrition in the form of protein, minerals, vitamins and fats, meeting people’s food needs and preferences as well as contributing to a rich diversity of food cultures around the world.

Seafood is also one of the most traded food commodities globally – and demand is growing due to increasing world population and increasing wealth. This has led to a new concept to describe seafood – “Blue Food” – so as to include seaweeds, algae and new plant-based products alongside fish and shellfish leading up to the UN 2021 Food Systems Summit. Unfortunately, whatever the merits of the concept, it obscures how and by who food from the sea is produced and consumed, and opens the way for large corporations to carve out new opportunities and displacing existing actors in the name of sustainability.

The UN Food Systems Summit intends to reshape food systems at the global level. It will launch bold new actions to transform the way the world produces and consumes food, as part of the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. The current state of food and agricultural systems is described as a “triple crisis” in which obesity, undernutrition, and climate change are decimating human and planetary health (The Lancet Commission on the Double Burden of Malnutrition). Dominant food and agricultural systems pose just as great a threat to the planet as they do to humans; the industrial food system is one of the largest contributors to climate change.

Sustaining seafood into the future and providing for the needs of a growing population will require a radical change in the way such food is produced and consumed. Proposals on how to transform and future proof our food systems will emerge from the UN Food Systems Summit – and we may not like what comes out.

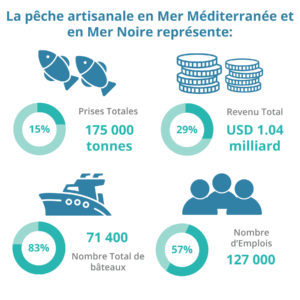

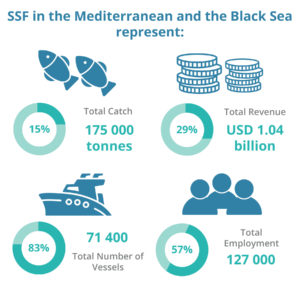

The theme of World Oceans Day – LIFE and Livelihoods – is therefore particularly relevant for the fishing sector, providing as it does tens of millions of livelihoods globally, directly and indirectly. According to the FAO as much as 10% of the world population relies on fisheries as a source of livelihoods, mainly eking out a living from small-scale fisheries in the global South.

However, unless it can respond to some immediate, urgent, and existential challenges, the fishing sector as we know it today, risks becoming an idiosyncrasy of the past. Nowhere is this more so than in Europe, where the EU’s Green Deal has set a high bar: a carbon neutral Europe by 2050, with a new action plan to conserve fisheries resources and protect marine ecosystems in the pipeline under the 2030 biodiversity strategy. This proposes a zero-tolerance approach to illegal practices, to limit the use of fishing gear most harmful to biodiversity, notably “bottom-contacting” fishing gear, and a crack-down on by-catch – especially threatened and endangered species.

One of the biggest existential challenges facing the European fishing sector is de-carbonization. Fossil fuels are the Achilles heel of the fishing sector, which it is currently able to access tax free. The economics of fishing is highly sensitive to the price of such fuel, as highlighted by the impact of fuel price hikes on profitability following the economic crises of the early 21st century. The EU’s Energy Taxation Directive is up for review in the framework of the Green Deal, and this tax break may be about to end. Likewise, rightly or wrongly, heavy dependence on hydrocarbon polymers for its equipment has brought fishing into disrepute with environmental organizations, who cite it as a major source of plastic waste in the marine environment and of ghost fishing – with lost gear described as the “tumbleweed of the oceans”, wreaking havoc on the ocean bed, blown along by ocean currents.

In the rush to decarbonise the economy and produce green energy, there is also increasing competition to use the oceans to develop the blue economy. Increasingly the fishing sector is having to compete for space at sea and is likely to face increasing restrictions of where it can fish as the blue economy develops. Priority may be given to green energy production over extracting fish, for example.

However, all these challenges become background noise if fishers’ access to resources and access to markets is not guaranteed – as is the case for Europe’s majority fleet. In Europe, as in other parts of the world, smaller scale, less environmentally impactful fishing operations represent the majority of the fleet by numbers, and often by employment. These relatively small-scale, near to shore operations supply fresh fish on a daily basis to local communities, providing jobs, livelihoods, food supplies and economic activities, often in areas where few alternatives exist.

Over the past several decades, successive Common Fisheries Policies (CFPs) have promoted larger scale more industrial fisheries in the interests of increasing production at the expense of smaller scale fishery activities. In particular subsidies have been poured into the development of larger scale fleets, which have also benefitted from the lion’s share of fishing rights.

The EU’s smaller scale fleets (vessels under 12 metres in length using non-towed gears) represent over 70% of the active vessels and 50% of the employment, but land only 5% of the catch by weight and 15% by value. This is in part due to the way the fishing rights allocation system in general and quota allocation system in particular have been unfairly rigged. The system favours the concentration of fishing rights into relatively few hands, with allocation based on catch history. This rewards those who fish more rather than those who fish more sustainably. This does not have to be so, but the practice continues, despite the 2014 CFP reform establishing the possibility to change the way fishing rights are allocated through the use of transparent and objective criteria, including those of an environmental, social and economic nature.

Likewise, despite the 2014 reform of the Common Marketing Policy (CMO) to favour small-scale producers establishing their own producer organizations (POs), small-scale fishers still confront huge barriers to forming their own POs.

SDG 14b), which makes the access of small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources and markets a priority must also form a central plank of the implementation of the CFP, and the review to be carried out in 2022 by the European Commission.

For its part, the Low Impact Fishers of Europe (LIFE) has joined hands with the MAVA Foundation, the Slow Food Foundation and the Global Footprint Network to launch the “Foodnected” project. This new project is designed to promote the transition to sustainable and fair food systems in the Mediterranean region. It is about “connecting people and nature around local, fair and sustainable food systems.” Its vision is to bring producers and consumers together through a Community of Practice grounded in shared values. By shortening the distance between producers and consumers and developing an ethical code of environmental and social values for the way food is produced and consumed, the project will address shortcomings in the prevailing market system and reverse the unfair situation faced by small-scale producers.

Smaller-scale, low impact fishing activities will never replace production from larger-scale activities. Both small-scale and large-scale sectors are needed to harvest fish sustainably to meet demands.

But the system could be a lot fairer and a lot more sustainable by allowing the small-scale sector to increase its share of the catch and the market. Such a move would also encourage a younger generation of fishers to take up fishing, particularly if its image can be portrayed as a modern sector compatible with a decent income and family life.

Consumers too can play their role by thinking globally and acting locally – by choosing fresh, locally produced fish, in season, coming from small-scale low impact fishing activities.

The old is dying, but without dedicated action the new cannot be born. The solutions are there, we must apply them.

Italy, March 4th, 2021 – Foodnected, a new project designed to promote the transition to sustainable and fair food systems in the Mediterranean region, will be launched on March 10 at a virtual event as part of the international festival Terra Madre Salone del Gusto, project partners Slow Food, Global Footprint Network, Low Impact Fishers of Europe (LIFE), and GOB Menorca announced today.

Italy, March 4th, 2021 – Foodnected, a new project designed to promote the transition to sustainable and fair food systems in the Mediterranean region, will be launched on March 10 at a virtual event as part of the international festival Terra Madre Salone del Gusto, project partners Slow Food, Global Footprint Network, Low Impact Fishers of Europe (LIFE), and GOB Menorca announced today. “Gaining fair access to resources and markets is a fundamental struggle for small-scale low-impact fishers who make up the majority of the European fleet. We believe that working together with others is essential to achieving a positive and meaningful change in our food systems. To be viable, fishers must be rewarded for the value they add through their good practices. On the other hand, consumers need to be able to easily identify sustainable, healthy and fair products, and to know their story, so they can value and select them,” said LIFE Executive Secretary Brian O’Riordan.

“Gaining fair access to resources and markets is a fundamental struggle for small-scale low-impact fishers who make up the majority of the European fleet. We believe that working together with others is essential to achieving a positive and meaningful change in our food systems. To be viable, fishers must be rewarded for the value they add through their good practices. On the other hand, consumers need to be able to easily identify sustainable, healthy and fair products, and to know their story, so they can value and select them,” said LIFE Executive Secretary Brian O’Riordan.

Antonis recently joined the LIFE Team as Project Manager for a new project in Cyprus. The project aims to engage small scale low impact fishers in the co-management of a Marine Protected Area in Chrysochou Bay through setting up a co-management committee with the competent authorities.

Antonis recently joined the LIFE Team as Project Manager for a new project in Cyprus. The project aims to engage small scale low impact fishers in the co-management of a Marine Protected Area in Chrysochou Bay through setting up a co-management committee with the competent authorities.