Crisis in the Mediterranean: Small Scale Fisheries must be included as part of the solution.

Crisis in the Mediterranean: Small Scale Fisheries

must be included as part of the solution.

Brussels, 20 april 2016

By Brian O’Riordan, Deputy Director

Low Impact Fishers of Europe (LIFE)

“Our patient is ill, but still breathing. The diagnosis is serious, but there is still hope.” From Commissioner Vella’s Opening Speech in Catania 9 February 2016, High level seminar on the Status of the Stocks in the Mediterranean and on the CFP Approach.

“Concerted effort needed to ensure that best practice become standard practices in small scale fisheries” – conclusion of GFCM Regional Conference on Small Scale Fisheries.

—————————————–

The Low Impact Fishers of Europe (LIFE) contend that if Mediterranean fisheries are to recover from their current crisis, small scale fisheries have to be included as a central part of the remedy.

Any solution to the crisis in the Mediterranean must be built around small scale fisheries, as this sector provides the social and economic backbone of fishing communities.

The oversight of the Spanish Government to include representatives from the small scale sector in their recent consultation with the fisheries sector, environmentalists, scientists and regional authorities must be remedied. Meeting in Madrid on April 7 to lay out details of its draft plan for the recovery of Mediterranean fisheries, the Fisheries Secretariat of the Ministry for Agriculture, Food and the Environment failed either to acknowledge the strategic importance of small scale fisheries to the success of such a plan, they also failed to invite representatives from the sector.

The Spanish plan is in preparation for a Ministerial conference in Brussels, hosted by DG Mare, on April 27, to coincide with the European Seafood Show (now called Seafood Expo Global). The meeting is spurred by the fishery crisis in the Mediterranean, and is the next step following the two day “high level seminar” on the state of stocks in the Mediterranean that took place in Catania, Sicily earlier this year. It will include Fisheries Ministers from all the countries bordering the Mediterranean, with the aim of agreeing on the actions necessary to address the crisis in the Mediterranean. Proposals from this conference will be taken to the 40th Session of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), the Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO) for the Mediterranean and Black Sea, on 30 May.

The importance of small scale coastal fisheries (SSCF) in the Mediterranean is highlighted by the 2014 Annual Economic Report on the EU Fishing Fleet by the Scientific and Technical Committee on Fisheries (STEFC). This finds that, according to the available data, for the Mediterranean & Black Sea fleet, the small scale fleet (SSF) possessed 69% of the fleet in number and accounted for 67% of the effort but provided jobs for only 51% of the total employed. In terms of production, the SSF landed only 13% in weight but 23% in value; overall generating 27% of the revenue.

Whilst emphasising the important social and economic weight of the sector, these figures also highlight the huge gap in the available data on landings. Any visitor to a Mediterranean fishing port will be impressed by the quantity of small boats, the quantities of fish they collectively land, and the availability of fresh locally caught fish in the nearby restaurants and retail outlets. Clearly their contribution to landings is higher than available data shows.

Mediterranean wide, according to the General Commission for Fisheries in the Mediterranean – the GFCM – SSCF “constitute over 80 percent of the fishing fleet, employ at least 60 percent of total on-vessel fishing labour and account for approximately 25 percent of the total landing value from capture fisheries in the region. At their best, small-scale fisheries exemplify sustainable resource use: exploiting living marine resources in a way that minimizes environmental degradation while maximizing economic and social benefits. Concerted effort is needed to ensure that best practices become standard practice.”

Small scale low impact activities using passive gears applied in a non-intensive and seasonally polyvalent manner also provide a ready-made solution to the problems of overfishing and environmental degradation caused by larger scale intensive, industrial fishery activities. Of course, considerable environmental impact is also being caused by the unrestricted use of small-meshed monofilament gillnets, and the associated effects of ghost fishing. Such irresponsible practices must be halted, in the same way that irresponsible industrial practices must be halted.

LIFE also contends that Article 17 of the CFP (“Basic Regulation” (EU) No 1380/2013) has an important role to play in favouring more sustainable ways of fishing, based on smaller scale, low impact fishing methods. Article 17, designed to promote responsible and socially beneficial fishing, obliges States to use transparent and objective criteria including those of an environmental, social and economic nature when allocating the fishing opportunities available to them. It also encourages States to provide incentives to fishing vessels deploying selective fishing gear or using fishing techniques with reduced environmental impact, such as reduced energy consumption or habitat damage.

At a meeting organized by LIFE in Athens on 28 November 2015, smaller scale fishers and their representative organisations from Greece, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, France and Spain demanded a greater voice in the development of fisheries policy at national and European levels. The meeting highlighted the need for the creation of long term plans as an integral element of the more dynamic and effective management of Mediterranean fisheries. Fishers also highlighted the need to reduce and then eventually eliminate pollution in the Mediterranean due to its a very significant adverse effect on coastal fisheries and the wider marine environment

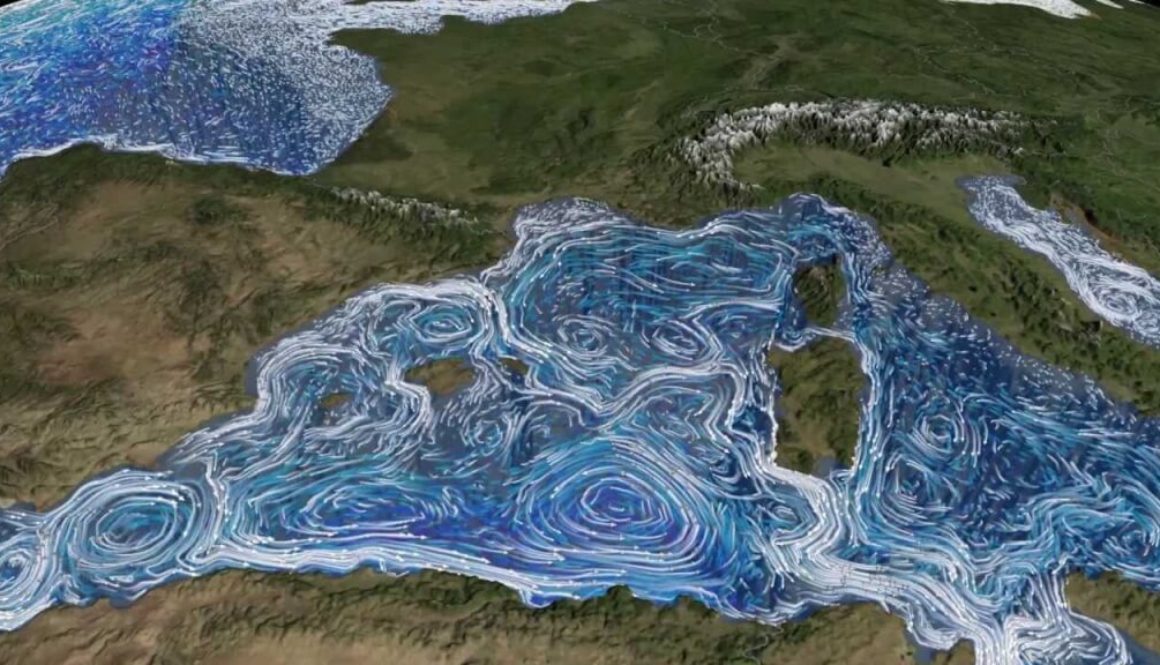

However, although fishery activities undoubtedly have a significant impact on fish stocks and on the marine habitats essential for fishery production, it would be incorrect to lay the entire blame for the fishery crisis in the Mediterranean on fishing alone. The Mediterranean is a semi-enclosed sea, and highly vulnerable to the impacts of human activities. Including Gibraltar and Monaco there are 23 countries bordering the Mediterranean, and the impacts of industrial and domestic sources of pollution are considerable, as are the impacts of port, shipping, and offshore oil and gas exploration and extraction, and the actual and potential impacts of climate change (including acidification, increases in extreme weather, sea level rise, warming of the sea etc.).

The Mediterranean also has a notorious reputation for illegal (IUU) fishing. Sometimes this is carried out under the guise of “sports fishing”, the impact of which is considerable. In addition, due to the complex nature of national maritime boundaries and inadequate monitoring, control and enforcement, much illegal, unregulated and unreported fishery activity takes place beyond national boundaries. In many cases these extend out to only 12 miles. There is also a lack of harmonized policies between EU Member States and other Mediterranean countries, hence the need for action at the RFMO level, in the GFCM.

The question also arises as to what extent fishery specific measures can be used to restore fish stocks and the marine environment, and to what extent a raft of much wider measures is needed. For example, MSY is unlikely to be achieved solely by applying such fishery specific measures as closed seasons, fleet capacity reductions, technical measures to reduce the impact of fishing gears, etc. Unless environmental degradation caused by pollutants, marine debris (including plastics), by acidification from increasing CO2 levels etc. is addressed, fish stocks will not be able to rebuild themselves to pre-crisis levels.

Except for professional fisheries, all traditional sectors of Mediterranean maritime economy such as tourism, shipping, aquaculture and offshore oil and gas are expected to keep growing during the coming 15 years. Comparatively new or emerging sectors such as renewable energy, seabed mining and biotechnology are expected to grow even faster, although there is greater uncertainty concerning these developments and their expected impacts on marine ecosystem.

For sure, the road to recovery will be paved with a complex array of difficulties. However, unless policy makers include small scale fisheries and the stakeholders from the sector in their plans and consultations, it will be a rocky road to nowhere.