umjetnost autora: Iris Maertens

Na UNOC-u 2022. mali ribari i predstavnici ribarskih zajednica sa 6 kontinenata održali su Poziv na akciju za inkluzivnu reformu upravljanja oceanima.

Mali ribari: najbrojniji korisnici oceana

Drugi Konferencija UN-a o oceanima (UNOC 2022.) održan u Lisabonu od 27. lipnja do 1. srpnja bio je posvećen potrebi očuvanja i održivog korištenja svjetskih oceana, mora i morskih resursa.

Ambicija UNOC-a 2022. postavljena je u Lisabonska (politička) deklaracija o našem oceanu, našoj budućnosti, našoj odgovornosti.

Fokus UNOC-a 2022. bio je analizirati kako se provodi Cilj održivog razvoja 14 (SDG 14), koji se odnosi na očuvanje života pod vodom i uključuje 10 ciljeva. Pokrenuti 2015. godine, s namjerom da se postignu do 2030. godine, 17 ciljeva održivog razvoja međusobno su povezani globalni ciljevi osmišljeni kao “nacrt za postizanje boljeg i održivijeg života za sve”.

Mali ribari (SSF) i obalne zajednice najbrojniji su korisnici oceana. Njihove aktivnosti malog ribarstva pružaju vitalni izvor hrane, sredstava za život, socioekonomskih i kulturnih koristi lokalno i pravedno milijunima ljudi diljem svijeta - posebno na globalnom Jugu.

Bliski odnosi SSF-a s morem i obalnim okolišem tijekom stoljeća pružaju im bogatu zalihu tradicionalnog znanja – Tradicionalnog ekološkog znanja (TEZ). Kroz svoje svakodnevne aktivnosti na moru i obali, mali ribari stječu uvid u funkcioniranje mora, o sezonskim promjenama u ribarstvu i drugim morskim resursima, vremenskim obrascima i povezanim pojavama. Ovo iskustveno znanje unapređuje njihove vještine kao pomoraca, proizvođača hrane i čuvara mora. To predstavlja masovno nedovoljno iskorištenu, ali potencijalno revolucionarnu bazu znanja. Zajedno, njihovo TEZ i iskustveno znanje čine dio bogate biokulturne raznolikosti, doprinoseći raznolikim kulturnim krajolicima i morskim pejzažima. Obrana i promicanje biokulturne raznolikosti ključno je za održivo korištenje prirodnih resursa u oceanima, morima i obalnim područjima.

Stoga je vrlo prikladno da malo ribarstvo ima posebno mjesto u ciljevima postavljenim za Cilj održivog razvoja 14. Cilj održivog razvoja 14b ima za cilj osigurati pristup morskim resursima i tržištima za male ribare.

Ljudski život iznad vode ovisi o održavanju zdravog života pod vodom

Očuvanje života pod vodom i održivo korištenje oceana, mora i morskih resursa ključni su za održavanje ljudskog života i dobrobiti iznad vode. UNOC 2022. u Lisabonu okupio je uglavnom dva glavna protagonista: one koji se zalažu za reforme u upravljanju oceanima kako bi se spasio naš ocean (tj. spasio ljudski život na našem planetu) i one koji se zalažu za reforme kako bi se otvorilo plavo gospodarstvo i utro put divovskim koracima u ulaganjima, industrijskom razvoju i stvaranju bogatstva, posebno u proizvodnji energije, vađenju minerala i živih resursa, proizvodnji hrane, bioistraživanju i brodarstvu.

Poziv na akciju

Prečesto su mali ribari (MRI) odsutni iz procesa donošenja odluka. Prečesto drugi, koji su udaljeni od svakodnevne stvarnosti malih ribara, iako možda s najboljim namjerama, govore u njihovo ime. Ti sugovornici neizbježno čine više štete nego koristi pogrešno predstavljajući MRI, čineći ih nevidljivima, oduzimajući im moć i ne savjetujući se s njima o onome što govore ili kako je ono što su rekli primljeno.

Stoga su mali ribari za Lisabonski UNOC 2022. željeli biti tamo osobno. “Razgovarajte s nama, ne za nas” i “nema ništa o nama bez nas”, sažmite što SSF misli o takvim sugovornicima. Ako im takvi sugovornici omoguće sudjelovanje, SSF je vrlo dobro sposoban izraziti vlastite zahtjeve, nade i strahove.

Tako se skupina od oko 20 predstavnika malog ribarstva (predstavnici SSF-a) sa 6 kontinenata – Oceanije, Azije, Afrike, Sjeverne i Južne Amerike te Europe – našla među otprilike 6000 službenih delegata koji su se registrirali za sudjelovanje na UNOC-u 2022. Uz podršku i koordinaciju koju je pružila mreža regionalnih organizacija civilnog društva (OCD), ovi su predstavnici mogli rano krenuti na put prema Lisabonu.

Organizacije uključene u ovaj proces uključivale su Lokalno upravljanu mrežu morskih područja (LMMA) iz Pacifika, Kesatuan Nelayan Tradisional Indonesia (KNTI) iz Indonezije, Federaciju obrtničkih ribara Indijskog oceana (FPAOI), Afričku konfederaciju profesionalnih organizacija obrtničkih ribara (CAOPA) i mezoameričku mrežu koja okuplja autohtone zajednice iz Kostarike, Paname, Hondurasa (Garifuna) i Meksika.

U tom nastojanju podržali su ih Koalicija za pravedne aranžmane u ribarstvu (CFFA), CoopeSoliDar RL i Blue Ventures.

Pozivu na akciju pridružile su se i druge SSF skupine iz Europe, Afrike i Latinske Amerike.

Početni rad uključivao je susrete i dijeljenje iskustava njihovog svakodnevnog života, radnih uvjeta te njihovih nada i strahova. To je omogućeno zahvaljujući stručnjacima za komunikaciju, prevođenje, facilitaciju i koordinaciju koji su radili uz ove radnike na prvoj crti kako bi im omogućili da se jasno izraze i da budu shvaćeni. Korak po korak počeli su graditi savez, temeljen na empatiji, povjerenju i međusobnom poštovanju, te razumjeti granice svog zajedničkog cilja. To je izraženo u njihovom Pozivu na djelovanje, koji poziva vlade da:

- Osigurati siguran i povlašten pristup zdravim oceanima i ekosustavima za male ribare

- Razviti znanstveno utemeljeno, transparentno, uključivo i participativno upravljanje ribarstvom;

- Rješavanje prijetnji koje predstavljaju onečišćenje i konkurencija industrija plavog gospodarstva;

- Ulagati u dugoročno upravljanje resursima, obnovu ekosustava i inovacije, gradeći na lokalnim inicijativama muškaraca i žena iz ribarskih zajednica.

- Razviti nacionalne strateške planove za provedbu 5 ključnih područja djelovanja do 2030. godine, uz odgovarajuće financiranje i vođene Smjernicama FAO-a za osiguranje održivog malog ribarstva i drugim relevantnim regionalnim politikama.

5 ključnih područja poziva su:

- Hitno osigurati povlašteni pristup SSF-u i zajedničko upravljanje 100% obalnim područjima.

- Jamčiti sudjelovanje žena, podržati njihovo osnaživanje i poticati priznavanje i poštovanje uloga koje imaju.

- Zaštitite malo ribarstvo od konkurentskih sektora plavog gospodarstva

- Uspostaviti transparentnost i odgovornost u upravljanju ribarstvom

- Izgraditi otpornost zajednica kako bi se suočile s prijetnjama klimatskih promjena i poboljšati izglede za mlade.

Doručak i Ocean's Base Camp

U pripremi za 3. dan UNOC-a 2022. i plenarnu sjednicu o ribarstvu – “Interaktivni dijalog o održivom ribarstvu i osiguravanju pristupa malog obrtničkog ribara morskim resursima i tržištima” – predstavnici SSF-a sastajali su se svakodnevno. Pripremni rad uključivao je dogovor o podjeli uloga i odgovornosti za širenje njihovog Poziva na djelovanje, sastanke s njihovim nacionalnim i regionalnim delegacijama radi traženja njihove podrške i kontaktiranje širih predstavnika civilnog društva radi podrške njihovom pozivu.

The sastanci za doručak omogućeni su zahvaljujući podršci ICCA konzorcija koji je osigurao prevođenje na 4 jezika i Zaklade Oceana Azul koja je rezervirala korištenje restorana Tejo u lisabonskom oceanariju za doručke.

Osim toga, portugalska koalicija nevladinih organizacija Sciaena, zajedno sa Zakladom Oceana Azul i organizacijom Seas at Risk, uspostavila je bazni kamp za oceane – https://oceanbasecamp.org/ – kao “sigurno utočište” za organizacije civilnog društva tijekom UNOC-a 2022. Bazni kamp pružio je prostor za ulazak, opuštanje, susrete, sudjelovanje u raspravama i nizu događaja tijekom tjedna.

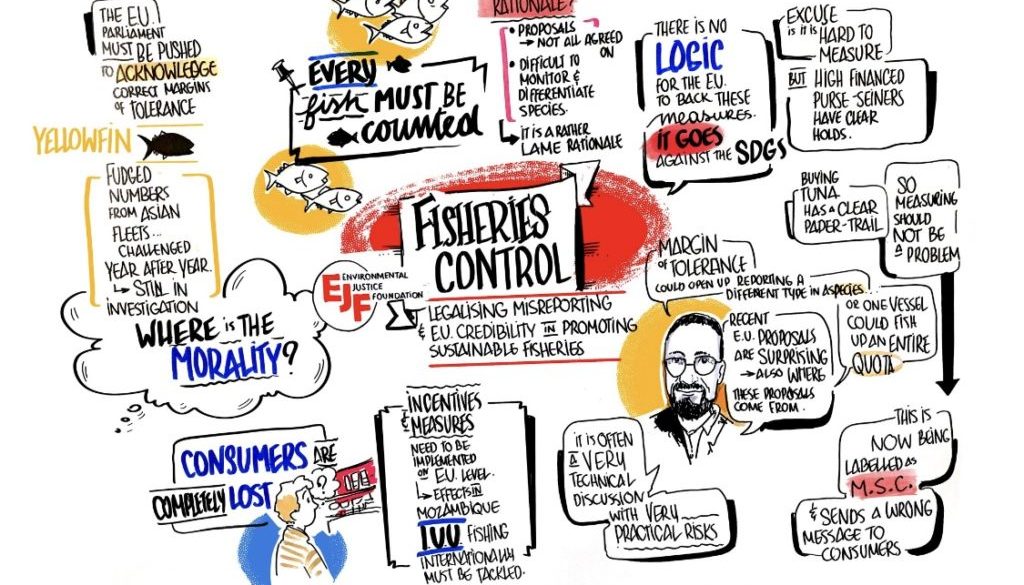

Vizualni zapis događaja i raspravljenih pitanja u stvarnom vremenu u sažetom obliku pružio je Iris Maertens iz Irisistible Designa koji joj je besplatno dao nevjerojatne vještine.

Prikladno, jedan od prvih događaja u Baznom kampu bio je na "“Moć partnerstava”, u kojem je autor sudjelovao. Moć partnerstava je u izgradnji sinergija i stvaranju saveza čije su kombinirane snage puno veće od zbroja pojedinačnih organizacijskih komponenti. Slabosti leže u potencijalno sukobljenim ciljevima između različitih partnera. Prečesto sukobljeni prioriteti i ciljevi narušavaju izgradnju sinergija i snažnih saveza. Pažljivo planiranje, izgradnja povjerenja i potpuna transparentnost su ključni.

Bazni kamp Ocean također je ugostio predstavnike SSF-a sa 6 kontinenata, koji su predstavili svoj Poziv na akciju.

Održivost ribarstva

Tjedan u Lisabonu bio je prepun frenetične aktivnosti, s mnogim neformalnim događajima, radionicama i sastancima koji su se održavali oko formalnih sjednica UNOC-a. Međutim, nedostatak prevođenja otežao je delegacijama SSF-a da se u njima smisleno uključe.

U jednom takvom događaju raspravljalo se o “Budućnost oceana: pronalaženje kooperativnih puteva prema 2030. godini”, moderator sastanka i arhitekt Zajedničke europske ribarstvene politike iz 2014., g. Ernesto Penas Lado, predložio je da oceanske aktivnosti moraju biti “legitimne i kompatibilne” kako bi se kvalificirale za prostor u nastajućem okviru upravljanja oceanima. Sukobljeni interesi morali bi se uključiti u smislen dijalog kako bi osigurali sve manje dijelove pristupa, pri čemu bi netradicionalni korisnici oceanskog prostora, na primjer, zadirali u tradicionalna ribolovna područja. Postojali bi pobjednici i gubitnici. Vivienne Sollis (CoopeSoliDar RL Costa Rica) govoreći u ime organizacija civilnog društva rekla je da takav okvir također mora biti pravedan. Trenutno mjesta za stolom pripadaju onima s najviše moći i utjecaja. To se mora promijeniti.

Dawda Saine, glavni tajnik CAOPA-e, primijetio je da ne postoji konsenzusni stav o tome što je zapravo plavo gospodarstvo. Zbog toga su mnogi SSF-ovi to nazvali “plavim strahom”. Ukratko, moderator je primijetio da moramo prijeći s plavog straha na plavo povjerenje, pri čemu su dijalog i uključivanje ključni za postizanje tog cilja.

U ime LMMA mreže, Lavenia Naivalu iz Fidžija, kao tradicionalna vođa svoje zajednice, istaknula je kako zajednice poput njezine u potpunosti ovise o ribljim resursima te surađuju na njihovom upravljanju i održavanju. Pozvala je na veću transparentnost i odgovornost, posebno kako bi se osiguralo prikupljanje rodno osjetljivih podataka i dostupnost informacija o ulozi žena, posebno u pogledu sigurnosti hrane, egzistencije i očuvanja prirode.

Javier Garat, predsjednik Međunarodne koalicije ribarskih udruga (ICFA) i europskog udruženja vlasnika ribarskih plovila Europech, rekao je da je ključno da obrtnički i industrijski ribari surađuju kako bi postigli sigurnost hrane održivim korištenjem morskih resursa. To je slično kao da predsjednik agrobiznisnih udruga poziva male poljoprivrednike koji se bave agroekologijom i tvrtke za industrijsku poljoprivredu na suradnju.

Udruga ribara s niskim utjecajem na okoliš (LIFE) odgovorila je da je spremna surađivati sa svima u konstruktivnom dijalogu, sve dok se priznaju povijesne nepravde koje su pretrpjeli manji ribari, a njihova prava na pravedan pristup resursima i tržištima odražavaju se u praktičnoj podršci i mjerama upravljanja, uz odgovarajuću zaštitu od zadiranja većeg ribolova i drugih konkurentskih aktivnosti.

Interaktivni dijalog

Nekoliko predstavnika SSF-a dobilo je dopuštenje da govore na plenarnoj sjednici na temu “Održivost ribarstva”. Josefina Mata iz Meksika, članica delegacije autohtonih zajednica iz Mezoamerike, snažno je govorila o ulozi žena, često glava samohranih roditeljskih kućanstava, koje se bore da osiguraju hranu i obrazuju svoju djecu, dok istovremeno obavljaju svoju egzistenciju. Iz Gvineje Conakry, predstavnica CAOPA-e, Antonia Adama Djalo predstavila je 5 prioriteta Poziva na akciju i zatražila da se u završnu deklaraciju doda odlomak kojim se ističe temeljna uloga malog ribarstva u iskorjenjivanju gladi i siromaštva te osiguravanju održivih sredstava za život i očuvanju morskih ekosustava; nadalje je pozvala da se u Lisabonskoj deklaraciji navedu prioritetne akcije koje vlade trebaju poduzeti kako bi osigurale da nastave doprinositi gospodarstvima, zdravlju, kulturi i dobrobiti.

Ribari iz Europe

Udruga ribara s niskim utjecajem na okoliš (LIFE) sudjelovala je s kolegama iz cijelog svijeta u izradi gore opisanog Poziva na djelovanje. U Europi se suočavamo s vrlo drugačijim skupom prijetnji, izazova i prilika u usporedbi s ribarima s niskim utjecajem na okoliš na jugu. Ovdje smo građani-potrošači, a naše potrebe zadovoljava tržište. Prema našoj kupovnoj moći, tržište nam pruža izbor prehrambenih proizvoda u svježem, cijelom ili prerađenom obliku. Naša sigurnost hrane ovisi o našoj kupovnoj moći i o tome što tržište nudi. To nas stavlja u vrlo ranjivu situaciju, s velikom ovisnošću o dugim, složenim, energetski intenzivnim i otpadnim lancima opskrbe te njihovim sustavima dostave "just-in-time". U Europi bi ribari s niskim utjecajem na okoliš mogli pomoći u poboljšanju i osiguranju situacije pružanjem svježe, zdrave i održive hrane u sezoni po poštenoj cijeni, lokalno, kako se zalaže i... Prehrambeno povezano projekt.

Europa je najveće tržište ribe na svijetu. Oko 7 od svakih 10 riba koje mi Europljani jedemo uvozi se, a gotovo 50% onoga što jedemo dolazi od 5 vrsta - lososa i škampa (uglavnom iz akvakulture s tolištima), bakalara, tune i aljaškog bakalara.

Kao i na jugu, SSF (pasivni alati, plovila ispod 12 metara) predstavljaju većinu sektora u smislu veličine flote, ali u smislu zaposlenosti i produktivnosti njegova dominacija postupno se smanjuje. Danas SSF u EU osigurava oko 50% radnih mjesta na moru, ali je ograničen na samo 5% ulova po volumenu. To znači da samo oko 15 grama od svakog kilograma ribe koju konzumiramo u Europi dolazi iz europskih aktivnosti malog ribolova.

U svom govoru na Interaktivnom dijalogu o održivom ribarstvu, Čarlina Vičeva, glavna direktorica Glavne uprave za more i ribarstvo Europske komisije, istaknula je da obrtnički ribolov u Europi predstavlja posebne izazove. “Pod malim ribolovom zapravo mislimo na ribolov iz malih brodova, što nije nužno održivo”, rekla je. “Da bismo ih učinili održivima, potrebno nam je mnogo podataka i kontrola kako bismo osigurali da se pridržavaju pravila.”

Nažalost, Europska komisija i mnoga nacionalna tijela još uvijek vide malo ribarstvo kao dio problema upravljanja ribarstvom, a ne kao dio rješenja. Označavanje malo ribarstvom kao “ribolov iz malih brodova koji nije nužno održiv” ne uzima u obzir da je malo ribarstvo sezonski raznolika, polivalentna aktivnost ukorijenjena u zajednicama, koja pruža društvene i ekonomske koristi u područjima s malo alternativa. Opća regulacija nije put naprijed. Takva regulacija kroz uzastopne zajedničke ribarstvene politike dovela je do propasti malo ribarstva u Europi.

Umjesto toga, LIFE zagovara “diferencirani pristup” upravljanju ribarstvom, s jedne strane za obrtnički ribolov, a s druge za industrijski ribolov. Takav pristup bi ogradio prava na ribolov malog ribarskog sektora (SSF), uspostavio zajedničko upravljanje ekskluzivnim ribolovnim zonama za SSF, pružio podršku organizacijskom i infrastrukturnom razvoju te osnažio ribare da postanu pokretači promjene sa suodgovornošću za održavanje europskih mora.

Međutim, plavi strah na koji se poziva CAOPA vrlo je stvarna i prisutna opasnost. U Europi, ciljevi EU-ovog Zelenog plana za proizvodnju energije na moru obvezuju se na povećanje kapaciteta s trenutnih razina od oko 12 GW na preko 300 GW do 2050. Također, postizanje klimatski neutralnog dekarboniziranog ribarskog sektora zahtijevat će radikalne promjene u tehnologiji, gospodarstvu i radnim praksama. Plava hrana također je čvrsto na jelovniku. Iako uglavnom nije definirana, ovo bi mogao biti tanak kraj klina za poticanje ekološki štetne akvakulture u našim obalnim vodama i utrti put industrijskoj proizvodnji i ekstrakciji morskih algi i morskih algi. Budućnost možda je plava, ali za SSF postoji malo optimizma da to daje ikakve osnove za plavu nadu.

UNOC 2022 bio je inspirativan i energičan događaj. Posebno je pružio mogućnost izgradnje značajnih sinergija s partnerskim udrugama i izgradnje saveza sa istomišljenim organizacijama iz cijelog svijeta. Pomogao nam je da skupimo snagu, koordiniramo se i pripremimo za nadolazeće izazove.

Završna Lisabonska deklaracija SSF grupe može se vidjeti ovdje.

Borbe se nastavljaju: Prekretnice na putu

Sustav UN-a nije savršen. Osmišljen je na demokratskim načelima kako bi države mogle sudjelovati u međunarodnim procesima donošenja odluka. Nije namijenjen nedržavnim akterima i organizacijama civilnog društva, ali postoje različiti mehanizmi za te subjekte kako bi pristupili procesima UN-a kao promatrači ili kao dio vladinih delegacija.

Godine 1984., Svjetska konferencija FAO-a o upravljanju i razvoju ribarstva nije imala uvjete za sudjelovanje malih ribara, unatoč najboljim namjerama. To je potaknulo pokret koji je doveo do organiziranja paralelne konferencije – Međunarodne konferencije ribarskih radnika i njihovih podupiratelja – gdje se okupilo 100 sudionika iz 34 nacionalnosti kako bi raspravljali o svojim problemima. Najmanje 50% bili su profesionalci u sektoru malog ribarstva – ribarski radnici. Ostalih 50% bili su podupiratelji – pojedinci ili nevladine organizacije koje nisu izravno profesionalno uključene u aktivnosti povezane s ribolovom.

Nadovezujući se na događaj u Rimu 1984., 1986., Međunarodni kolektiv za podršku ribarima (ICSF) pokrenuli su “podupiratelji ribarskih radnika” u Trivandrumu u Indiji kako bi se riješili problemi na međunarodnoj razini koji utječu na SSF na nacionalnoj i lokalnoj razini. ICSF bi djelovao na dokumentiranju i stavljanju na raspolaganje informacija o problemima koji utječu na SSF, te bi, gdje je to prikladno, pokretao kampanje i organizirao događaje za raspravu o takvim problemima s predstavnicima SSF-a.

Godine 1997. u New Delhiju u Indiji pokrenut je Svjetski forum ribara i radnika u ribarstvu (WFF). Forum je imao za cilj predstavljati one koji se izravno bave ribolovom, preradom, prodajom i prijevozom ribe u sektorima opskrbe, obrtničkom, starosjedilačkom i tradicionalnom sektoru.

Godine 2000. WFF je odlučio podijeliti se u dvije skupine - WFF i Svjetski forum ribara (WFFP), obje sa sličnim ciljevima onima definiranim 1997. godine.

Proces izrade Dobrovoljnih smjernica FAO-a o osiguravanju održivog malog ribarstva u kontekstu sigurnosti hrane i iskorjenjivanja siromaštva (VGSSF) uključio je ICSF, WFF i WFFP u intenzivnu suradnju koja je rezultirala njihovim usvajanjem 2014. godine. Proces je olakšao Međunarodni odbor za planiranje za Suverenitet hrane (IPC), subjekt sa sjedištem u Rimu koji olakšava uključivanje organizacija civilnog društva u procese FAO-a vezane uz pitanja proizvodnje hrane.

4000 subjekata bilo je uključeno u procese povezane s VGSSF-om. Istodobno, pojavile su se brojne druge nacionalne, regionalne i transnacionalne strukture povezane sa SSF-om, neke povezane s WFF-om, WFFP-om i IPC-om, dok su druge formirale različite saveze.

Bogata raznolikost aktera na međunarodnoj razini možda odražava bogatu raznolikost ribarskih zajednica malog ribarstva diljem svijeta. Nadamo se da će ova raznolika skupina aktera moći raditi na podršci zajedničkom cilju malog ribarstva.