Mediteran

Plavorepna tuna u Sredozemnom moru: dobre vijesti zasjenjene tamnim oblakom.

Plavorepna tuna u Sredozemnom moru: dobre vijesti zasjenjene tamnim oblakom.

Barcelona, 31. svibnja 2016.

Platforma LIFE

DG Mare nedavno je najavio otvaranje sezone ribolova plavoperajne tune (http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/mare/itemdetail.cfm?type=880&typeName=Press%20Release&item_id=31694). Ali iza ove dobre vijesti krije se Mračna priča o društvenoj nepravdi i propuštenoj prilici. Stotine polivalentnih malih ribara u Sredozemlju koji su tradicionalno lovili plavoperajnu tunu tijekom dvomjesečne do tromjesečne sezone ručnim udicom, pri čemu je svaki ribar u prosjeku ulovio jednu ribu, efektivno su isključeni iz ribolova.

Na vidjelo izlazi slučaj za slučajem diskriminacije manjih ribara od strane nepravedna raspodjela kvota sustave diljem EU-a koji su u suprotnosti s održivošću i socijalnom pravdom. Nigdje to nije više slučaj nego u slučaju plavoperajne tune u Sredozemnom moru.

Članak 17. Zajedničke ribarstvene politike – Uredba (EU) br. 1380/2013 – zahtijeva da države koriste “transparentne i objektivne kriterije, uključujući one ekološke, društvene i ekonomske prirode” prilikom dodjele ribolovnih mogućnosti. Međutim, od svih mogućih kriterija navedenih u članku, države članice i dalje koriste povijesni rekordi gotovo isključivo za dodjelu kvota. Povijesno gledano, u većini slučajeva, mali ribari nisu bili obvezni voditi evidenciju ulova, pa tako ni nepravedno diskriminiran protiv kojeg se bori ovaj sustav.

Članak 17. također potiče države članice da daju poticaje “ribarskim plovilima koja koriste selektivni ribolovni alat ili tehnike ribolova sa smanjenim utjecajem na okoliš, kao što je smanjena potrošnja energije ili oštećenje staništa” unutar ribolovnih mogućnosti koje su im dodijeljene. Takva bi se odredba mogla koristiti za nagrada malog opsega, ekološki prihvatljive i društveno važne ribarske aktivnosti, ali i dalje miruje.

Međutim, provedba potencijalno revolucionarnih odredbi članka 17. zahtijeva političku volju za promjenu pristupa “uobičajenog poslovanja”. Povijesno gledano, ZRP je bila slijepa na mali ribolov. To je značilo da je njezin fokus bio na reguliranju većeg ribolova mobilnim alatima. Dakle, iznova i iznova, manje ribarske operacije s malim utjecajem bile su nepravedno diskriminirane, unatoč njihovim inherentnim društvenim, ekonomskim i ekološkim prednostima.

Tuna: sjajan primjer u tmurnom Mediteranu.

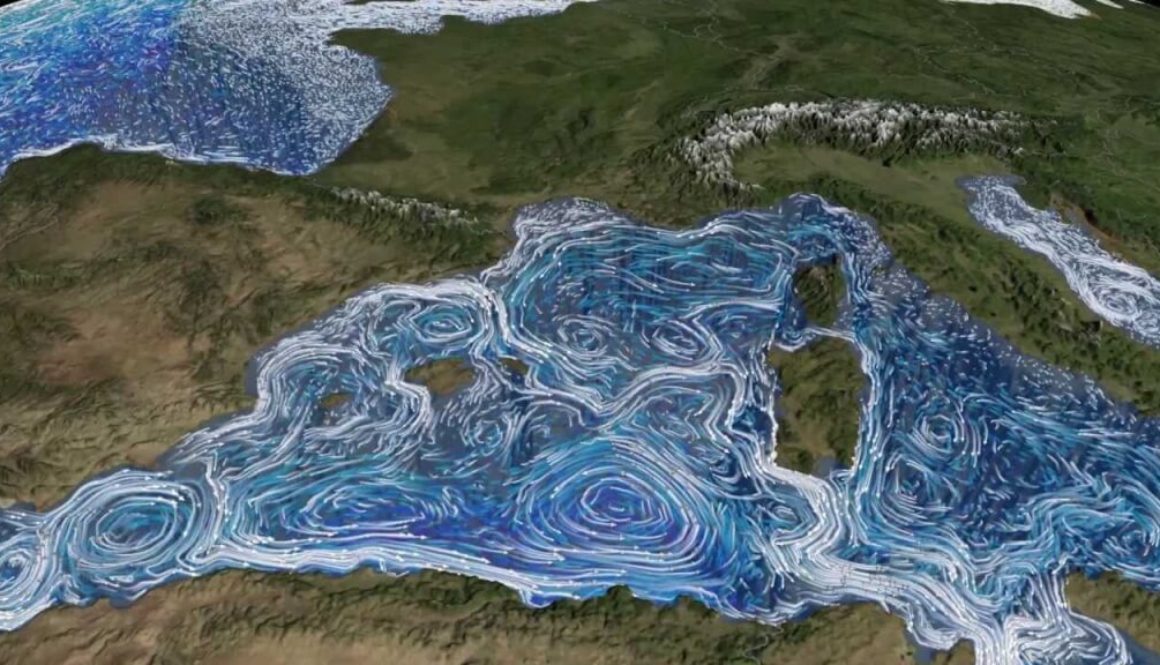

U Sredozemnom moru, oporavak populacije plavoperajne tune jarko se ističe nasuprot sumornoj pozadini prekomjernog izlova koji je izmakao kontroli. Općenito, sredozemne riblje zalihe su u ozbiljno iscrpljenom stanju, a procjenjuje se da je 93% tih zaliha prekomjerno izlovljeno.

Godine 2006. smatralo se da je plavoperajna tuna na rubu izumiranja. izumiranje. Iako je prerano reći da su zalihe atlantske plavoperajne tune sada dosegle održive razine, znakovi njihovog oporavka dobro govore za desetke komercijalnih ribljih zaliha u Sredozemnom moru koje su u stagnaciji.

Znanstveni savjeti pokazuju da se populacija atlantske plavoperajne tune oporavlja, što je potaknulo Međunarodnu komisiju za očuvanje atlantskih tuna (ICCAT) – međunarodno tijelo odgovorno za regulaciju ribolova atlantske (uključujući i mediteransku) tune – da uspostavi Povećanje ukupnog TAC-a od 60% za plavoperajnu tunu tijekom trogodišnjeg razdoblja od 2015. do 2017. Zahvaljujući tome, u 2016. europski TAC za plavoperajnu tunu iznosi 11 203 tone.

Odluka ICCAT-a također se temelji na poboljšanjima u kontroli nezakonit, neprijavljen i nereguliran (NNN) ribolov zahvaljujući korištenju novih tehnologija i međunarodne suradnje, kao i nizu mjera upravljanja usvojenih od 2006. kao dio plana oporavka plavoperajne tune za istočni Atlantik i Sredozemno more.

Tamna strana ove dobre vijesti je da su one ribolovne operacije koje su imale i nastavljaju imati najveći utjecaj na resurs nagrađene dodatna kvota – upravo suprotno od onoga što bi Članak 17. trebao biti. U međuvremenu, manji ribari s niskim utjecajem na Sredozemlje, koji su lovili tunu od predaka, uz značajne iznimke, bivaju izostavljen iz ove velike kvote. Ove manje operacije imaju minimalan utjecaj na resurse, ali potencijalno imaju značajne društvene i ekonomske koristi za zajednice koje ovise o ribolovu.

Oni koji ubiru korist su u biti veći ribarski brodovi s plivaricama koji love tunu živu za tov, relativno noviju komercijalnu aktivnost koja se oslanja na korištenje malih pelagičnih vrsta za prehranu. Mnoge od tih malih pelagičnih vrsta prekomjerno se love, posebno u Sredozemnom moru.

Također postoji zabrinjavajući znak da ovo darivanje kvota velikim ribarskim tvrtkama pretvara javni resurs u privatnu robu putem prenosivih individualnih (ili plovila) kvota (ITQ). Na primjer, španjolski zakoni sada dopuštaju privremeni ili trajni prijenos kvota za tunu između plovila s pristupom ribolovu tune, što bi moglo dovesti do koncentracije kvote dodijeljene velikim i srednjim plovilima u rukama nekoliko tvrtki, kao i što je dovelo do spekulativnih ulaganja i trgovine kvotama za tunu.

ŽIVOT odbacuje takav model dodjele ribolovnih prava, bilo u Sredozemlju ili negdje drugdje. Ribarstvo je globalna baština i nacionalne vlade, a ne privatne tvrtke, odgovorne su za upravljanje time tko ima pristup tim prirodno obnovljivim resursima i tko ih koristi. Komercijalizacija ribljih stokova putem ITQ-ova i sličnih tržišno utemeljenih alata za upravljanje ribarstvom nije ni poštena ni održiva.

ŽIVOT poziva vlade država članica da primijene članak 17. ZRP-a, i slovom i duhom zakona. To znači primjenu članka 17. kako bi se potaknulo promicanje odgovornog i društveno korisnog ribolova. Besplatno davanje ribolovnih prava malom broju sve prosperitetnijih i moćnijih ribarskih tvrtki oduzelo je većinu flote i pretvara javno dobro u privatno vlasništvo.

♦♦♦

Kriza u Sredozemlju: Malo ribarstvo mora biti uključeno kao dio rješenja.

Kriza u Sredozemlju: Malo ribarstvo

mora biti uključen kao dio rješenja.

Bruxelles, 20. travnja 2016.

Od Briana O'Riordana, zamjenika ravnatelja

Ribari s niskim utjecajem na okoliš u Europi (LIFE)

"Naš pacijent je bolestan, ali još diše. Dijagnoza je ozbiljna, ali još uvijek ima nade..”Iz uvodnog govora povjerenika Velle u Cataniji 9. veljače 2016., Seminar na visokoj razini o stanju stokova u Sredozemlju i o pristupu ZRP-a.“.

"Potrebni su usklađeni napori kako bi se osiguralo da najbolje prakse postanu standardne prakse u malom ribolovu” – zaključak Regionalne konferencije GFCM-a o malom ribolovu.

——————————————–

Europski ribari s niskim utjecajem na okoliš (LIFE) tvrde da ako se sredozemno ribarstvo želi oporaviti od trenutne krize, malo ribarstvo mora biti uključeno kao središnji dio lijeka.

Svako rješenje krize u Sredozemlju mora se temeljiti na malom ribarstvu, jer taj sektor pruža društvenu i ekonomsku okosnicu ribarskih zajednica.

The nadzor španjolske vlade uključivanje predstavnika malog ribarstva u njihove nedavne konzultacije s ribarskim sektorom, ekolozima, znanstvenicima i regionalnim vlastima mora se ispraviti. Na sastanku u Madridu 7. travnja kako bi se iznijeli detalji njegovog nacrta plana za oporavak sredozemnog ribarstva, Tajništvo za ribarstvo Ministarstva poljoprivrede, hrane i okoliša nije priznalo stratešku važnost malog ribarstva za uspjeh takvog plana, niti nije pozvao predstavnike iz sektora.

Španjolski plan je u pripremi za ministarsku konferenciju u Bruxellesu, koju će organizirati DG Mare, 27. travnja, a koja će se poklopiti s Europskim sajmom morskih plodova (sada nazvanim Globalni sajam morskih plodova). Sastanak je potaknut krizom ribarstva u Sredozemlju i sljedeći je korak nakon dvodnevnog “seminara na visokoj razini” o stanju ribljih stokova u Sredozemlju koji se održao Catania, Sicilija ranije ove godine. Uključivat će ministre ribarstva iz svih zemalja koje graniče sa Sredozemljem, s ciljem dogovora o akcijama potrebnim za rješavanje krize u Sredozemlju. Prijedlozi s ove konferencije bit će odveden do 40ti Zasjedanje Opće komisije za ribarstvo Sredozemlja (GFCM), Regionalne organizacije za upravljanje ribarstvom (RFMO) za Sredozemno i Crno more, 30. svibnja.

Važnost malog obalnog ribolova (SSCF) u Sredozemlju istaknuta je u Godišnjem gospodarskom izvješću o ribarskoj floti EU za 2014. godinu koje je izradio Znanstveni i tehnički odbor za ribarstvo (STEFC). U njemu se navodi da je, prema dostupnim podacima, za sredozemnu i crnomorsku flotu, Mala flota (SSF) posjedovala je 691 TP3T flote po broju i činila je 671 TP3T napora, ali je osiguravala radna mjesta za samo 511 TP3T ukupnog broja zaposlenih. Što se tiče proizvodnje, SSF je ulovio samo 131 TP3T po težini, ali 231 TP3T po vrijednosti; ukupno je generirao 271 TP3T prihoda.

Iako naglašavaju važnu društvenu i ekonomsku težinu sektora, ove brojke također ukazuju na ogroman nedostatak dostupnih podataka o iskrcajima. Svaki posjetitelj sredozemne ribarske luke bit će impresioniran količinom malih brodova, količinama ribe koju zajedno iskrcavaju i dostupnošću svježe lokalno ulovljene ribe u obližnjim restoranima i maloprodajnim mjestima. Jasno je da je njihov doprinos iskrcajima veći nego što pokazuju dostupni podaci.

Sredozemno more, prema Opća komisija za ribarstvo u Sredozemlju – GFCM – SSCF "čine preko 80 posto ribarske flote, zapošljavaju najmanje 60 posto ukupne ribarske radne snage na plovilu i čine otprilike 25 posto ukupne vrijednosti iskrcaja iz ribolova u regiji. U najboljem slučaju, mali ribolov primjer je održivog korištenja resursa: iskorištavanja živih morskih resursa na način koji minimizira degradaciju okoliša, a istovremeno maksimizira ekonomske i društvene koristi. Potrebni su usklađeni napori kako bi se osiguralo da najbolje prakse postanu standardna praksa.”

Male aktivnosti s niskim utjecajem koje koriste pasivnu opremu primijenjenu na neintenzivan i sezonski polivalentan način također pružaju gotovo rješenje za probleme prekomjernog izlova ribe i degradacije okoliša uzrokovane intenzivnim industrijskim ribolovnim aktivnostima većih razmjera. Naravno, znatan utjecaj na okoliš uzrokuje i neograničena upotreba monofilamentnih mreža s malim okcima i povezani učinci "fantomskog ribolova". Takve neodgovorne prakse moraju se zaustaviti, na isti način na koji se moraju zaustaviti neodgovorne industrijske prakse.

ŽIVOT također tvrdi da Članak 17. ZRP-a (“Osnovna uredba” (EU) br. 1380/2013) ima važnu ulogu u poticanju održivijih načina ribolova, temeljenih na metodama ribolova manjeg opsega s niskim utjecajem. Članak 17., osmišljen kako bi se potaknuo odgovoran i društveno koristan ribolov, obvezuje države da koriste transparentne i objektivne kriterije, uključujući one ekološke, društvene i ekonomske prirode, prilikom dodjele ribolovnih mogućnosti koje su im dostupne. Također potiče države da daju poticaje ribarskim plovilima koja koriste selektivni ribolovni alat ili tehnike ribolova sa smanjenim utjecajem na okoliš, kao što su smanjena potrošnja energije ili oštećenje staništa.

Na sastanku koji je organizirao ŽIVOT U Ateni su 28. studenog 2015. manji ribari i njihove predstavničke organizacije iz Grčke, Hrvatske, Italije, Cipra, Francuske i Španjolske zatražili veći utjecaj na razvoj ribarske politike na nacionalnoj i europskoj razini. Na sastanku je istaknuta potreba za izradom dugoročnih planova kao sastavni element dinamičnijeg i učinkovitijeg upravljanja ribarstvom u Sredozemnom moru. Ribari također istaknuto potreba za smanjenjem, a zatim i na kraju uklanjanjem zagađenje u Sredozemnom moru zbog vrlo značajnog negativnog utjecaja na obalno ribarstvo i širi morski okoliš

Međutim, iako ribarske aktivnosti nesumnjivo imaju značajan utjecaj na riblje zalihe i morska staništa bitna za ribarsku proizvodnju, bilo bi netočno smatrati Sva krivnja za ribarsku krizu u Sredozemlju pripisuje se isključivo ribarstvu. Mediteran je poluzatvoreno more i vrlo je osjetljiv na utjecaje ljudskih aktivnosti. Uključujući Gibraltar i Monako, postoje 23 zemlje koje graniče sa Mediteranom, a utjecaji Industrijski i kućni izvori onečišćenja su značajni, kao i utjecaji luka, brodarstva i istraživanja i vađenja nafte i plina na moru, te stvarni i potencijalni utjecaji klimatskih promjena. (uključujući zakiseljavanje, porast ekstremnih vremenskih uvjeta, porast razine mora, zagrijavanje mora itd.).

Mediteran također ima zloglasnu reputaciju za ilegalni (NN) ribolov. Ponekad se to provodi pod krinkom “sportskog ribolova”, čiji je utjecaj znatan. Osim toga, zbog složene prirode nacionalnih pomorskih granica i neadekvatnog praćenja, kontrole i provedbe, velik dio ilegalnih, nereguliranih i neprijavljenih ribolovnih aktivnosti odvija se izvan nacionalnih granica. U mnogim slučajevima one se protežu na samo 12 milja. Također nedostaje usklađenih politika između država članica EU-a i drugih mediteranskih zemalja, stoga je potrebno djelovanje na razini regionalnih organizacija za upravljanje ribarstvom (RFMO), u okviru GFCM-a.

Također se postavlja pitanje u kojoj mjeri se mjere specifične za ribarstvo mogu koristiti za obnovu ribljih stokova i morskog okoliša, a u kojoj mjeri je potreban niz mnogo širih mjera. Na primjer., Malo je vjerojatno da će se MSY postići isključivo primjenom mjera specifičnih za ribarstvo kao što su sezona zabrane ribolova, smanjenje kapaciteta flote, tehničke mjere za smanjenje utjecaja ribolovnih alata itd. Ukoliko se ne riješi problem degradacije okoliša uzrokovane zagađivačima, morskim otpadom (uključujući plastiku), zakiseljavanjem zbog povećanja razine CO2 itd., riblji fond neće se moći obnoviti na razinu prije krize.

Osim profesionalnog ribarstva, očekuje se da će svi tradicionalni sektori mediteranskog pomorskog gospodarstva poput turizma, brodarstva, akvakulture te nafte i plina na moru nastaviti rasti tijekom sljedećih 15 godina. Očekuje se da će relativno novi ili sektori u nastajanju, poput obnovljivih izvora energije, rudarstva morskog dna i biotehnologije, rasti još brže, iako postoji veća neizvjesnost u vezi s tim razvojem i njihovim očekivanim utjecajem na morski ekosustav.

Zasigurno će put do oporavka biti popločan nizom složenih poteškoća. Međutim, ako kreatori politika u svoje planove i konzultacije ne uključe malo ribarstvo i dionike iz sektora, to će biti trnovit put bez ikakvog smjera.

LIFE sudjeluje na regionalnoj konferenciji GFCM-a na temu “Izgradnja budućnosti za održivo malo ribarstvo u Sredozemnom i Crnom moru”.

Bruxelles, 14. ožujka 2016.

LIFE sudjeluje na regionalnoj konferenciji GFCM-a o

“Izgradnja budućnosti za održivo malo ribarstvo u Sredozemnom i Crnom moru”.

Sastanku Opće komisije za ribarstvo Sredozemlja, koji se održao od 7. do 9. ožujka 2015. u Alžiru (Alžir), prisustvovali su Brian O'Riordan, zamjenik direktora programa LIFE, i Marta Cavallé, koordinatorica programa LIFE za Sredozemlje.br.

Svrha sudjelovanja LIFE-a na sastanku bila je podizanje svijesti o ŽIVOT, njegovu misiju i ciljeve, kako bi se istaknula pitanja važna za male europske ribare s niskim utjecajem na okoliš i kako bi se kontakti to će pomoći ŽIVOT i njegov rad kako bi postao šire prepoznat i podržan.

Konkretno, Brian O'Riordan je predstavljao ŽIVOT na okruglom stolu o Dobrovoljnim smjernicama FAO-a za osiguranje malog ribolova (Smjernice SSF), gdje se njegov doprinos usredotočio na prilike i izazovi za male europske ribare s niskim utjecajem u provedbi reformirane ZRP-e.

Opća komisija za ribarstvo Sredozemlja (GFCM) je regionalna organizacija za upravljanje ribarstvom (RFMO) i stoga igra važnu ulogu u upravljanju ribarstvom u regiji. Prisustvovanje takvom sastanku stoga je u potpunosti u skladu s ŽIVOT’cilj je “obnoviti zdravlje naših mora u Europi i ostatku svijeta”. Treba podsjetiti da se Sredozemlje suočava s kritičnom situacijom prekomjerni izlov i iscrpljeni stokovi, nedostatak učinkovitog upravljanja, nezakoniti, neregulirani i neregulirani ribolov, degradacija okoliša i tako dalje. Glavna uprava za ribarstvo i ribarstvo nedavno je organizirala hitan sastanak o stanju ribljih stokova u Sredozemnom moru te će 27. travnja 2016. biti domaćin ministarskog sastanka o ribarstvu svih sredozemnih država u Bruxellesu.

Sastanku su prisustvovale delegacije iz sjevernoafričkih zemalja, Europske komisije (DG Mare) i MedAC-a, neke europske delegacije, sjevernoafričke ribarske organizacije, WWF, IUCN i razne nevladine organizacije te istraživači.

Jedna od glavnih tema sastanka bila je podrška održivi razvoj malog ribarstva putem Plavog rasta. “Plavi rast” ima za cilj maksimizirati ekonomske prinose od iskorištavanja mora i oceana u ravnoteži s ekološkom održivošću i društvenim razvojem. To je novi koncept utemeljen na Rio procesu o održivom razvoju, povezan sa zelenim gospodarstvom. Široko se promiče i moglo bi ozbiljno utjecati na malo ribarstvo. Plavi rast daje prednost onim sektorima s najvećim potencijalom za rast i ekonomske koristi.

Konzultant koji je vodio raspravu istaknuo je da ribarstvo nisu vidljivi U makroekonomskom pogledu na plavi rast. Malo je prostora za povećanje proizvodnje u ribarstvu. Što se njega tiče, ribarstvo treba pokazati kako može maksimizirati svoj doprinos gospodarstvu i rastu te se u skladu s tim “prepozicionirati”. To bi, rekao je, zahtijevalo a) primjenu sustava “prava korištenja” radi postizanja ekonomske učinkovitosti i b) stvaranje “investibilnog viška” koji bi se mogao uložiti u rast.

Konzultant koji je vodio raspravu istaknuo je da ribarstvo nisu vidljivi U makroekonomskom pogledu na plavi rast. Malo je prostora za povećanje proizvodnje u ribarstvu. Što se njega tiče, ribarstvo treba pokazati kako može maksimizirati svoj doprinos gospodarstvu i rastu te se u skladu s tim “prepozicionirati”. To bi, rekao je, zahtijevalo a) primjenu sustava “prava korištenja” radi postizanja ekonomske učinkovitosti i b) stvaranje “investibilnog viška” koji bi se mogao uložiti u rast.

Sljedeće dvije sesije vodili su projekti povezani s WWF-om, prvu zajedničko upravljanje i drugi na Zaštićena morska područja i kako bi se njihova učinkovitost mogla poboljšati sudjelovanjem malog ribolova u njihovom upravljanju i korištenju. Prezentacije su također istaknule potrebu za “zonama zabrane ulova” u zaštićenim morskim područjima kako bi se povećala njihova produktivnost.

WWF ima znatno relevantno iskustvo u Sredozemlju s zaštićenim morskim područjima (MPA) i angažmanom u malom ribolovu putem projekta MedPan. Kontaktirali smo predstavnike MedPana/WWF-a kako bismo istražili kako bi članovi programa LIFE mogli imati koristi od obuke i druge podrške kako bi ih ribarske vlasti u zaštićenim područjima bolje razumjele. Predloženo nam je da ŽIVOT organizirati delegaciju koja će prisustvovati 2.i Forum zaštićenih morskih područja u Sredozemlju, koji će se održati u Tangeru u Maroku od 29. studenog do 1. prosinca 2016.

Na četvrtoj sjednici raspravljalo se lanci vrijednosti u malom ribolovu i kako ga promovirati na načine koji ribarima omogućuju korist od dodane vrijednosti. Jedan od ključnih problema s kojima se suočavaju mali ribari je visoka cijena koju njihova riba postiže na tržištu u usporedbi s relativno niskom cijenom koju dobivaju. Raspravljalo se o raznim programima, uključujući zadruge, osposobljavanje, ekooznake itd.

Posljednji panel na kojem je sudjelovao Brian O'Riordan bavio se Smjernicama FAO-a o malom ribarstvu, a njegova prezentacija bila je o prilikama i izazovima za malo ribarstvo u provedbi ZRP-a u Sredozemlju, ističući izazove s kojima se suočava zaboravljena europska flota i mogućnosti Članak 17., Uredba o tržištu, EFPR i savjetodavna vijeća.

Glavni zaključci konferencije sadržani su u dokumentu od 7 stranica, koji predlaže osnivanje radna skupina za malo ribarstvo u kojoj bi LIFE mogao sudjelovati.GFCM je bio vrlo pozitivan u vezi ŽIVOT’sudjelovanje i bili su vrlo podržavajući ideju ŽIVOT prisustvovanje sastancima GFCM-a.

Osoblje LIFE-a imalo je sastanke s mnogim različitim ljudima i organizacijama, uključujući:

Abdella Srour, izvršna tajnica, GFCM.

Stefano Cataudella, predsjednik GFCM-a.

Valerie Laine, DG Mare, voditeljica Odjela za očuvanje i kontrolu u Sredozemlju.

Rosa Caggiano, izvršna tajnica, MedAC.

Dr. Vassiliki Vassilopoulou, direktorica istraživanja, Helenski centar za istraživanje mora

Matthieu Bernardon, konzultant za ribarstvo pri FAO-u i drugima, sa značajnim iskustvom u sscf-u u Mediteranu.

Giuseppe Di Carlo, voditelj jedinice MPA, WWF Mediteranski program

Julien Sémelin, voditelj programa, Program za mediteranski bazen, Zaklada MAVA.

Fabrizio De Pascale, nacionalni tajnik, Talijanski sindikat radnika, ribarstvo i akvakultura

Margaux Favret, Vijeće za upravljanje morskim resursima, projekt Medfish.

Hacene Hamdani i drugi s platforme za obrtničke ribare Magrebije (zajedno s drugim ribarima iz regije).

Predstavnici španjolskih vlasti.