Upravljanje

Gušenje zbog obveze iskrcavanja

Gušenje zbog obveze iskrcavanja:

pomiješane poruke, teška pitanja i različita mišljenja u Bruxellesu

Bruxelles, 31. svibnja 2018.

Brian O'Riordan

Obveza iskrcavanja (LO) je jedna od najdalekosežnijih i najkontroverznijih mjera koje su uvedene u reformiranu Zajedničku ribarstvenu politiku (ZRP) iz 2013. Osmišljen kako bi se riješila i etička (bacanje hrane) i pitanja očuvanja (selektivnost/prekomjerni izlov), došao je kao grom iz vedra neba nakon vrlo energične kampanje usmjerene i na širu javnost i na europske donositelje odluka, a koju su vodile televizijske osobe. Uopće nije bio predviđen u Zelenoj knjizi iz 2009., a malo je vremena posvećeno razradi načina na koji bi se takva mjera mogla provesti u praksi. Preferirani pristup DG Mare provedbi bio je postupno uvođenje LO-a tijekom razdoblja od 4 godine (2015. do 2019.), rješavajući probleme kako se pojavljuju, umjesto da se pokušavaju predvidjeti i riješiti problemi unaprijed.

Tri i pol godine od početka provedbe, a samo 7 mjeseci do potpunog stupanja na snagu, nadamo se da je do sada većina nedostataka na LO-u izglađena.

To je bio dojam koji je ostavio gospodin Karmenu Vella, povjerenik za pomorske poslove i ribarstvo, u govoru pred Odborom za ribarstvo Europskog parlamenta 15. svibnja. Istaknuo je da: „Pravila su jasna: od 1. siječnja 2019. obveza iskrcavanja primjenjivat će se na sve ulove vrsta koje podliježu ograničenjima ulova, a u Sredozemnom moru i minimalnim veličinama. To su pravila ZRP-a, o kojima su se svi dogovorili i koja su svima dobro poznata već više od četiri godine. Pravila se ne mogu mijenjati tijekom poluvremena utakmice... To bi potkopalo reformirani ZRP. I naštetilo bi našem kredibilitetu."..."

Međutim, takva jasnoća vizije i svrhe nedostajali su u raspravama u Europskom parlamentu prethodnog dana tijekom radionice na temu „Obveza iskrcavanja i vrste koje guše u viševrstnom i miješanom ribolovu“. Nakon prezentacije i rasprava o 3 studije slučaja iz sjeverozapadnih voda, Sjevernog mora i jugozapadnih voda, predsjednik Odbora za ribarstvo Alain Cadec sažeo je rekavši da: Dijagnoza je vrlo jasna: neizvjesnost, teškoća, složenost… Ne žalim što sam glasao protiv obveze iskrcavanja.".

Niti jedan od 9 zastupnika u Europskom parlamentu koji su govorili tijekom rasprave nije branio obvezu iskrcavanja (LO). Jedan je istaknuo da znanstvenici nisu ponudili nikakva rješenja te da se LO ne može primijeniti 1. siječnja 2019. Drugi je govorio o zbunjenosti i problemima te pozvao na dulje prijelazno razdoblje i veću fleksibilnost. Treći je izjavio da LO nije kompatibilan sa sustavom ukupnog dopuštenog ulova [TAC] / kvota te da ga je teško uskladiti s miješanim ribolovom. Čak se pozvao i na Plan B.

Predstavnik DG Mare složio se da postoji nesigurnost i kaos, ali je izrazio mišljenje da „Alat“ LO-a (zamjene/fleksibilnost kvota, de minimis odredbe, povećanja TAC-a, izuzeća itd.) ne koristi se dovoljno. Zastupnik je također primijetio da znanstvenici ne mogu dati potpunu sliku problema gušenja;prigušnice se ne guše jer LO još nije u potpunosti implementiran„S obzirom na to da se LO provodi postupno, potrebno je više vremena i strpljenja kako bi se vidjelo kako će se stvari razvijati, te je potrebno na LO gledati „drugačije“, zaključila je.

Slučaj Sjevernog mora istaknula je složenost definiranja specifičnih ribolovnih područja, kategoriziranih prema velikom rasponu metarija, godišnjih doba, vrsta itd. Izlagačica, francuska znanstvenica, istaknula je da ribolovna smrtnost u Sjevernom moru ponovno raste te da bi se prošli dobici mogli izgubiti. Također je napomenula da će problemi s gušenjem postati problem samo ako se LO strogo provodi. Trenutno problemi s gušenjem nisu uočeni niti prijavljeni STECF-u, što je ona uočila.

Slučaj jugozapadnih voda istaknuo je da će kombinacija FMSY-a i LO-a stvoriti ozbiljne probleme i zatvoriti ribarstvo. Uočeno je da je gušenje dinamično pitanje, posebno s obzirom na klimatske promjene. Utjecaj gušenja mijenjao bi se s vremenom – složena situacija koja će vjerojatno ostati složena, zaključeno je.

Zastupnici u Europskom parlamentu postavili su razna pitanja, uključujući i jedno od galicijskog zastupnika u Europskom parlamentu o utjecaj LO-a na malo ribarstvo s obzirom na nejednakost u raspodjeli kvota. U Galiciji, najvažnijoj europskoj ribarskoj regiji i regiji koja najviše ovisi o ribarstvu, 90% od 4500 ribarskih plovila klasificirano je kao „artes menores“, što obuhvaća plovila prosječne duljine 8,8 metara koja koriste pasivne alate. Većina tih plovila djeluje u mješovitom ribolovu, gdje se nalaze i vrste koje podliježu kvoti i one koje ne podliježu kvoti.

Međutim, kao i u drugim europskim državama članicama, flota malih plovila s pasivnom opremom ima ograničen pristup kvotama jer floti nedostaje potrebna povijest ulova da bi se kvalificirala za njih. Upravljanje kvotama uvedeno je kao mjera za veće flote i sada se nameće malim flotama putem Zakona o lojalnosti (LO), unatoč tome što je većina kvote dodijeljena većoj floti. Zbog toga je upravljanje kvotama, a time i LO, nepravedno diskriminirajuće prema manjim plovilima.

Također je postavljeno pitanje u ime škotskih operatera pridnenih koćarica, za koje je bakalar jedna od glavnih ciljnih vrsta i na koje će gušenje imati velike posljedice. Pitali su koji „stup“ ZRP-a treba žrtvovati – razine ribolova utvrđene na razini najvećeg održivog prinosa, provedbu LO-a ili ribare.

Prezentatorica slučaja Sjevernog mora primijetila je da ukidanje LO-a neće ništa riješiti, da se problem odbacivanja ulova neće riješiti sam od sebe. LO je, po njenom mišljenju, bio koristan alat za podizanje svijesti o problemu odbacivanja ulova, ali sada je bilo vrijeme da se sagledaju dva različita, ali povezana cilja:

a) želja za smanjenjem odbačenog ulova i

b) želja za izvlačenjem svih ulova.

Potonje se često smatra najgorom opcijom, ali nekontrolirano odbacivanje ulova također znači nekontrolirani ribolovni napor. Smatrala je da „Točno dokumentiranje odbačenog ulova na moru ima veći prioritet za postizanje održivosti od obveze iskrcavanja. SVE ulovljena riba„Što se tiče malog ribolova (MSF), smatrala je da je provedeno mnogo istraživanja i da se pitanje odbacivanja ulova u SSF-u može sažeti u maksimu da su, poput djece, mali brodovi = mali problemi, veliki brodovi = veliki problemi. Takvo gledište ne odražava se u različitim stvarnostima s kojima se različite flote moraju nositi, posebno ograničenom lokacijom i sezonskom prirodom malog ribolova u usporedbi s vrlo mobilnom prirodom, širim rasponom i cjelogodišnjom aktivnošću većih operacija. Bilo da su velike ili male po veličini, LIFE smatra da je za sve segmente flote prijetnja neposrednog bankrota veliki problem, bez obzira na veličinu plovila.

Takvo je stajalište izrazio španjolski znanstvenik predstavljajući slučaj jugozapadnih voda. Smatrao je da su, budući da su SSF i LSF prilično različiti, za svaki segment flote potreban drugačiji pristup.

Izlagač za sjeverozapadne vode, irski znanstvenik, odgovorio je na škotsko pitanje rekavši da ako sektor ribarstva ne lovi ribu na održiv način, ne radi se o odustajanju od ribara, već o tome da će ribari izgubiti svoja tržišta zbog pritiska potrošača. To je bio izbor koji je smatrao; ili se pridržavati Ugovora o ribolovu ili izgubiti svoja tržišta. Što se tiče malog ribarskog sektora (SSF), raspodjela je nacionalno pitanje, smatrao je, a na državama je da odluče kako će dodijeliti kvote i postupati s malim ribljim sektorom (SSF).

Prema mišljenju Udruge ribara s niskim utjecajem na okoliš (LIFE), LO će imati nesrazmjeran utjecaj na ribolovne operacije malog polivalentnog pasivnog ribolovnog alata (plovila kraća od 12 metara koja koriste nevučene alate). Uglavnom, ove su operacije vrlo selektivne, s vrlo niskim stopama odbacivanja ulova u usporedbi s koćarenjem i drugim vučenim alatima. Samo zato što je manje odbacivanja ulova u malom ribarskom području (SSF) ne znači da su manje pogođeni LO-om. LO je sigurno osmišljen imajući na umu sektor mobilnih alata velikih razmjera, a ne sektor pasivnih alata niskog utjecaja. To se odražava u činjenici da je u posljednjih nekoliko desetljeća objavljeno 3924 znanstvena rada vezana uz pitanja odbacivanja ulova, 3760 se usredotočilo na operacije velikih razmjera, a samo 164 je razmatralo implikacije za SSF.

Nedostatak pristupa malih ribara kvotama potrebnim za ostanak u održivosti kada se LO u potpunosti provede 2019. godine čini ih vrlo ranjivima na „gušenje“ i prisiljavanje na ukidanje poslovanja i bankrot ili na kršenje zakona i suočavanje s posljedicama. Što se tiče malog ribarskog fonda (SSF), LIFE se boji da bi politika nultog odbacivanja mogla postati politika nultog ribolova i nultog prihoda za SSF.

Stoga LIFE zagovara dvostruki pristup visini napora za ribolov male ribe (SSF). Prije svega, potrebno je osigurati potrebnu i pravednu raspodjelu kvota kako bi se SSF-u omogućilo planiranje i upravljanje svojim poslovanjem. Takva raspodjela trebala bi uključivati određeno objedinjavanje kvota koje se mogu koristiti po potrebi za rješavanje problema gušenja kada se pojavi. Drugo, za obalni segment flote SSF-a, prelazak na upravljanje naporom mogao bi pružiti pravedniji i učinkovitiji način rješavanja problema pristupa i odbacivanja ulova.

Dodatne informacije:

Vellin govor Parlamentu sljedećeg dana https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/vella/announcements/speech-commissioner-vella-european-parliament-pech-committee_en

Informacije o DGMareu: https://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/cfp/fishing_rules/discards/

Radionica Odbora za ribolov o obvezi iskrcavanja i vrstama koje se guše: https://research4committees.blog/2018/05/28/pech-workshop-landing-obligation-and-choke-species-in-multispecies-and-mixed-fisheries-2/

Malo ribarstvo i cilj nultog odbacivanja ulova. Glavna uprava Europskog parlamenta za unutarnju politiku. 2015. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/540360/IPOL_STU(2015)540360_EN.pdf

♦ ♦ ♦

Doprinos članova iz Španjolske o Planu upravljanja za mediteransku obalu - ENG/ES

Organizacije članice programa LIFE u Španjolskoj predstavljaju izmjene i dopune „Sveobuhvatnog plana upravljanja za očuvanje ribolovnih resursa pogođenih ribolovom koji se provodi mrežama plivaricom, koćama i pasivnim alatima na sredozemnoj obali Španjolske“.

Službenom PR-u na engleskom/španjolskom jeziku možete pristupiti ovdje.

Službeni dokument na ES-u možete pronaći ovdje

Las organizaciones miembro de LIFE en el mediterráneo español presentan alegaciones al “Plan de Gestión Integral para la conservación de los recursos pesqueros en el Mediterráneo afectados por las pesquerías realizadas con redes de cerco, redes de arrastre y artes fijos y menores”.

Acceda a la Nota de prensa oficial en ENG / ES aquí

Acceda al documento oficial en ES aquí

Raste zabrinutost zbog ribolova električnim pulsom

Raste zabrinutost zbog ribolova električnim pulsom

Utorak, 5. rujna

Jeremy Percy

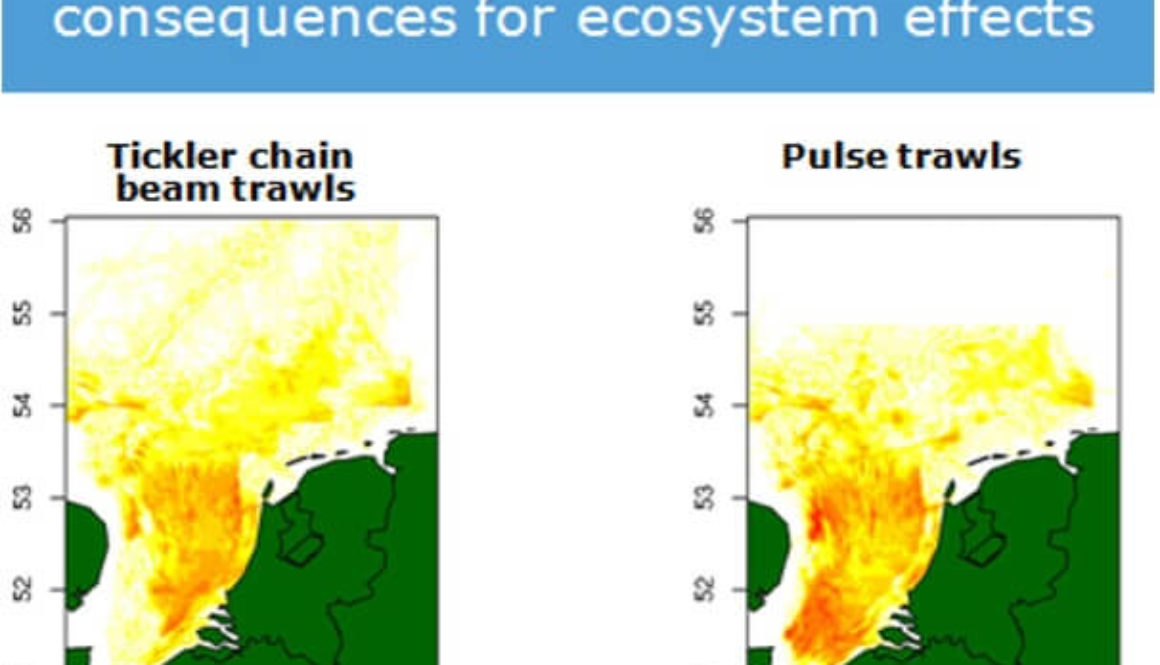

Sastanak u Nieuwpoortu u Belgiji 1. rujna, koji je organizirao belgijski obalni ribar Jan De Jonghe, a kojem su prisustvovali razni komercijalni ribari iz Ujedinjenog Kraljevstva, Belgije i Nizozemske, kao i osoblje Platforme ribara s niskim utjecajem na okoliš [LIFE] i istraživači iz Morskog instituta., istaknuo je sve veću zabrinutost zbog negativnih utjecaja masovnog i nekontroliranog porasta električnih pulsirajućih projektora u južnom dijelu Sjevernog mora. Delegacija sa sastanka kasnije se sastala s visokom dužnosnicom nizozemske vlade, gđom. Beom Deetman, odgovornom za europske ribolovne dozvole i propise. Električne pulsne koće rade ono što piše na pakiranju, ispaljuju električne impulse u morsko dno i to učinkovito zamjenjuje posao koji lanci za golicanje obično obavljaju kako bi gurali ribu prema gore i na putanju mreže. Korištena oprema je puno lakša od tradicionalnih koća s gredom, troši manje goriva za vuču, čini se da lovi više lista nego iverka i ima puno niže stope prilova.

Zasad je sve u redu, ali unatoč prosvjedima ribara koji koriste pulseve da se izlazni signali u smislu oblika i snage pulsa mogu i jesu strogo kontrolirani, zapažanja drugih ribara i znanstvenika proturječe izraženom mišljenju da to ne šteti ni meti ni drugim vrstama na i u morskom dnu.

Upotreba električne energije [kao i otrova i eksploziva] posebno je zabranjena Zajedničkom ribarskom politikom, tako da svi oni koji trenutno koriste ovu opremu [nizozemski nacionalni, a potom i britanski brodovi] posluju pod izuzećem Europske komisije. Imali su koristi od izvornog odstupanja za 5% flote koćarskih mreža s gredom država članica, u nekim slučajevima uz vrlo značajnu financijsku potporu Europe, a taj se broj zatim dramatično povećao maštovitom primjenom članka 14. nove Zajedničke ribarstvene politike koji navodi da “Države članice mogu provoditi pilot projekte, na temelju najboljih dostupnih znanstvenih savjeta i uzimajući u obzir mišljenja relevantnih savjetodavnih vijeća, s ciljem potpunog istraživanja svih izvedivih metoda za izbjegavanje, minimiziranje i uklanjanje neželjenih ulova u ribolovnom području”.

Ono što je sasvim jasno jest da je došlo do nedovoljno istraživanja i učinkovitih ispitivanja pred Komisijom, nizozemska vlada i ribari s koćarskim mrežama s gredom su se s obje noge uključili na temelju očite koristi metode [posebno za profitne marže]. Trenutni broj pulsirajućih brodova s koćom je znatno veći od stotinu i vjerojatno se povećava s fokusom napora na južnom dijelu Sjevernog mora. Slike u nastavku ilustriraju migraciju onoga što su nekada bili brodovi s koćama s koćom pretvoreni u pulsni ribolov na prethodno neribolovna područja uz Temzu.

Na sastanku se čulo svjedočanstva raznih ribara, a svi su istaknuli da je došlo do drastičan pad broja lista, bakalara i brancina Od uvođenja ribolova pulsirajućim glodavcem u velikim razmjerima prije 3 godine, neki su izvijestili da su vidjeli i izvukli velike količine mrtve ribe. Neki su južno Sjeverno more nazvali mrtvom zonom. Drugi su spomenuli da su jedine ribe koje su vidjeli bile (pjegave) morske pse i raže.

Izražene zabrinutosti su zapravo sažete u bilješci koju je napisao Tom Brown iz Udruge ribara Ramsgatea, čiji je sažetak reproduciran u nastavku:

“U estuariju Temze imamo područje između Knocka i Fallsa koje je odmah izvan naše granice od 12 milja.“. [vidi slike gore. Ed] U prošlosti tradicionalne koće s gredom nisu mogle tamo raditi zbog mekog tla, imali smo samo povremene francuske koće. Međutim, posljednje četiri godine preplavljeni smo koćaricama Pulse. Ovo područje nam je dobro poznato kao područje hranjenja lista u Doveru za estuarij Temze. Zimi, kada se more ohladi, list se kreće prema dubokoj vodi i zakopava se u blato. Pojavom koćarica Pulse postali su ranjivi. Kad su koće s gredom Pulse prvi put lovile u ovom području, nisu mogle vjerovati koliko to može biti unosno, toliko da su žurile natrag u luku, mijenjale posadu i ponovno se vraćale. Povrh svega, hvalile su se time na radiju.

Četiri godine kasnije, estuarij Temze gotovo je ostao bez ribe, do te mjere da je niz ribara prestao s radom, a broj brodova koji su lovili ribu u estuariju opao je. Moguće je da je to djelomično zbog pretjeranog jaružanja koje se provodi na Temzi, ali siguran sam da i pulsno koćarenje igra svoju ulogu.

Naši lokalni brodovi primijetili su da tamo gdje rade Pulse koće ima uginulih školjkaša, morskih zvijezda i malih miješanih riba. Čini se da pri radu u dubokoj vodi mogu pojačati struju, a u plitkoj je smanjiti kako ne bi oštetili druge ribe. Navedeni smo na razumijevanje da se, kako bi se maksimizirala sposobnost ulova, snaga stalno pojačava. Ne stojimo na putu napretka, ali to ne smije biti na štetu okoliša i drugih ribara.

Obavještavaju nas da je pulsni ribolov do 3 puta učinkovitiji od normalnog ribolova. Ako je to slučaj, hoće li zemlje koje provode pulsni ribolov smanjiti svoj ribolovni napor proporcionalno? Ako se pulsni koćarski ribolov uvede diljem EU kako bi se spriječilo tehničko širenje problema, pretpostavljam da će svi morati smanjiti svoj ribolovni napor u skladu s tim kako bi ostali unutar trenutnih parametara i ne bi ponovno uništili stokove.

Konkretni komentari lokalnih ribara uključuju:

- “To je kao da pecate na groblju nakon što su pulsne koće bile u tom području, gotovo sve je mrtvo”

- “Ovo je za nas apsolutno porazno jer nikada nismo ulovili toliko ribe koja je već bila mrtva.”

- “Tamo pecam već 30 godina i nikad nisam vidio ništa slično [ribolov na električni pogon].“.

- “Samo sjede tamo, usisavaju Sole i čekaju da se popnu uz Temzu kako bi se mrijestili.”

- “Rekli smo našim vlastima da su štetu uzrokovale električne koće, ali nam nisu vjerovali”

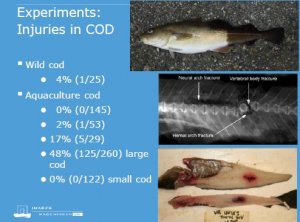

Nisu zabrinuti samo obalni ribari s juga Sjevernog mora. Radna skupina ICES-a za električni koćarski ribolov sastali su se tri puta (22.–24.10.2014.; 10.–12.11.2015. i 17.–19.01.2017.) kako bi raspravljali o tekućim istraživačkim projektima u Belgiji, Nizozemskoj i Njemačkoj te pružili pregled najsuvremenijih saznanja o ekološkim učincima. U njihovom završnom izvješću navodi se: ‘Puls lista primjenjuje višu frekvenciju koja izaziva grčeve koji imobiliziraju vrste riba, olakšavajući proces ulova. Korištenje električne energije u ribolovu izazvalo je znatnu zabrinutost među dionicima, a uglavnom se usredotočuje na nepoznate učinke na morske organizme i funkcioniranje bentoskog ekosustava, ali i na promijenjene ribolovne napore i učinkovitost ulova’. Dalje se navodi da je ‘……… Izloženost podražajima pulsa lista izazvala prijelome kralježaka i povezana krvarenja kod okruglih vrsta riba (bakalar), ali ne i kod plosnatih riba (list, iverak, livan) ili brancin. Rezultati sugeriraju da su prijelomi ograničeni na veće klase bakalara koje se zadržavaju u mreži….’

Izvješće zaključuje da “iako se čini da su nepovratni učinci električne stimulacije ograničeni na prijelome kralježaka kod bakalara i oslića, potrebna su daljnja istraživanja o učincima električne stimulacije na morske organizme i funkcioniranje ekosustava procijeniti učinke na razmjere Sjevernog mora”

Ovi komentari naglašavaju zabrinutost izraženu na sastanku. Duh je izašao iz boce i unatoč jasnim dokazima, i znanstvenim i anegdotskim, da postoje značajni negativni utjecaji ribolova električnim pulsom, čini se da nema smanjenja navale upravitelja i ribara s grednim koćama na ovu vrstu alata.

Ostaje za vidjeti što će javnost misliti o ribi na svom tanjuru koja je bila ubijena strujom i slomljena u ime povećanja profita i smanjenja fizičkog utjecaja, iako neki od većih kupaca trenutno izbjegavaju kupnju proizvoda dobivenih elektrošokovima.

Kao što Tom Brownova bilješka jasno pokazuje, povećana upotreba ribolova električnim pulsom od strane sve većeg broja velikih plovila nesumnjivo ima negativan utjecaj na stokove, posebno one koji prije nisu bili ulovljeni. Iako postoji argument da je ribolovni napor, na bilo koji način, u konačnici kontroliran kvotom, sposobnost električnih prijenosnika da usmjere napor na relativno malo područje je zabrinjavajuća, kao i nepoznati i moguće dugoročni učinci na širi morski ekosustav.

Nitko zapravo ne očekuje da će Komisija povući svoju trenutnu derogaciju, ali svakako bi trebala djelovati sada sadrže napor, prostorno, numerički i u smislu učinkovitog upravljanja utjecajima sve dok se ne provede znatno više istraživanja o potencijalno štetnim aspektima ovog oblika ribolova.

Ako smo išta trebali naučiti iz katastrofalnih propusta upravljanja ribarstvom tijekom dva stoljeća, to je da se nikakva kratkoročna dobit za nekolicinu ne smije koristiti kao razlog ili izgovor za ignoriranje dugoročnih utjecaja i prava većine.

Službena svjedočanstva sa sastanka možete pronaći ovdje

♦ ♦ ♦

Pitanje ravnoteže

Pitanje ravnoteže:

Male i velike flote mogle bi igrati komplementarne uloge

s obzirom na jednake uvjete.

Bruxelles, 20. lipnja 2017.

Brian O'Riordan

Samo po sebi je očito da postoji mjesto i potreba za malim i većim ribarskim flotama, ali to prije svega zahtijeva uspostavljanje jednaki uvjeti za sve koji osigurava pravedan pristup resursima, tržištima, podršci sektoru i procesima donošenja odluka za sve segmente flote.

Kad je povjerenik Vella pitao LIFE jesu li sve aktivnosti malog ribolova u Sredozemnom i Crnom moru doista s malim utjecajem, već je sam odgovorio na svoje pitanje. Ranije u svom govoru dionicima ribarstva na Malti 29. ožujka 2017., europski povjerenik za pomorstvo i ribarstvo istaknuo je da 80% sredozemne “flote pripada malim ribarima (s plovilima kraćim od 10 m), koji love četvrtinu ukupnog ulova”. To znači da, prema povjereniku Velli, samo 20% flote, veći segment, uzima 75% ulova, te stoga ima daleko veći utjecaj na riblje zalihe i morski okoliš od 80% flote s 25% ulova.[1].

Naravno, nisu sve aktivnosti malog opsega malog utjecaja, a nisu ni svi ribolovi većeg opsega destruktivni. Zalihe mogu biti ranjivije tijekom određenih sezona kada se okupljaju radi mriješćenja, hranjenja i razvoja. I male i velike aktivnosti usmjerene na ove agregacije može imati značajan utjecaj na njih. Visoke koncentracije male ribolovne opreme u priobalnim vodama, na primjer, unatoč tome što se koristi s vrlo malih [<6 m] plovila, mogu imati veliki utjecaj na te agregacije. Isto tako, relativno mala plovila opremljena modernom tehnologijom za pronalaženje i navigaciju ribe, tegljačima za ribolovnu opremu i snažnim motorima, koja intenzivno love ribu, također mogu imati znatan utjecaj. Mala plovila, kao i velika, također zahtijevaju učinkovito upravljanje i regulaciju, ali iste regulatorne i upravljačke mjere nisu nužno prikladne za ova dva segmenta flote.

Mala veličina može biti pokazatelj održivosti, budući da mala veličina u smislu ribarstva podrazumijeva korištenje alata s malim utjecajem na okoliš, plovila s relativno niskim ugljičnim otiskom, s aktivnostima utemeljenim na obalnim zajednicama. od strane malih obiteljskih poduzeća koji osiguravaju radna mjesta i prihode u područjima s malo ekonomskih ili radnih alternativa, i gdje žene igraju ključnu ulogu, iako često nevidljivu i ekonomski nenagrađenu. Svakako je istina da je plovilu koje vuče koću veličine nogometnog igrališta, sa snagom motora koja se mjeri u tisućama kilovata, ili ribarici s poticačem koja koristi tešku metalnu žicu umjesto tradicionalnih užadi, puno lakše napraviti puno više štete, puno brže od prosječnog malog plovila.

U tom smislu, članovi Europske platforme “Ribari niskog utjecaja u Europi (LIFE)” teže ostvarivanju što manjeg utjecaja na riblje zalihe i ribolovna područja usvajanjem pristupa najbolje prakse. – korištenje prave opreme, u pravo vrijeme, na pravom mjestu. Naš odgovor na pitanje gospodina Velle je stoga: “Ne, naravno da ne. Nisu sve aktivnosti malog ribolova niskog utjecaja, ali mogli bi biti ako im se pruži poštena prilika i odgovarajuća podrška"..."

LIFE je oduvijek smatrao da su potrebne i velike (LSF) i male (SSF) ribolovne aktivnosti, u svim fazama opskrbnog lanca od ulova do potrošnje, te da igraju komplementarne uloge u osiguravanju prihoda, zapošljavanja i opskrbe hranom, stvaranju bogatstva te doprinosu kulturi i društvenoj dobrobiti obalnih zajednica. Zalihe dalje od obale mogu učinkovitije loviti veći brodovi koji se mogu sigurno nositi s uvjetima na moru i imaju kapacitet skladištenja većeg ulova. Iskrcaj velikih količina iz većih flota može biti prikladniji za velike pogone za preradu koji opskrbljuju masovna maloprodajna tržišta. Istodobno, postoje prednosti rezerviranja obalnih područja za manje operatere fiksne opreme, koji su tradicionalno opskrbljivali lokalna i specijalizirana tržišta visokokvalitetnom svježom ribom. Ovi obalni ribari i ribarstva također... podupiru brojne ranjive obalne zajednice, često s malo alternativnih mogućnosti zapošljavanja, ne samo u smislu proizvodnje hrane već i zbog dodane vrijednosti koju donose turističkom iskustvu, značajnog broja radnih mjesta na kopnu koja podržavaju i održavanja znanja i vještina povezanih s pomorstvom.

Doista je u interesu svih da se prepozna intrinzična komplementarnost između velikih i malih, obrtničkih i industrijskih flota, te između tradicionalnih i modernih aktivnosti, te da se identificiraju i iskoriste sinergije. To se može učiniti samo ako se uspostave jednaki uvjeti gdje konkurencija i sukobi ne stavljaju jedan ili drugi sektor u nepovoljan položaj, gdje se svakom segmentu flote osigurava pravedan i transparentan udio prava pristupa, gdje se nagrađuje dobra praksa i potiču inovacije.

To također zahtijeva sustav upravljanja koji one koji se bave ribolovom i aktivni su u lancu opskrbe stavlja u središte pozornosti, omogućujući im...o smisleno sudjelovati u procesima donošenja odluka koji utječu i na njih i na resurse o kojima ovise. Takvi sustavi upravljanja postoje i zahtijevaju da vlasti i ribari zajedno sjede u odborima za zajedničko upravljanje kako bi rješavali probleme i zajednički dogovarali smjerove djelovanja, pri čemu su ti odbori u potpunosti ovlašteni od strane uprave putem formalnih postupaka decentralizacije ovlasti. Pozdravlja se činjenica da Vlada Katalonije sada donosi takav zakon o zajedničkom upravljanju putem nove uredbe http://international-view.cat/2017/05/23/its-the-governance-stupid/.

Nasuprot tome, ribarstvo u Europi već više od 30 godina regulirano je Zajedničkom ribarskom politikom (ZRP), politikom koja je ignorirala mali ribolov, tretirajući ga kao nacionalno pitanje i praveći iznimke za manja plovila od mnogih pravila EU. To se pokazalo kao otrovana čaša za sektor malog ribolova, koji je zapravo često djelovao ispod regulatornog radara. To je značilo da Ulovi iz tog sektora nisu bili pravilno zabilježeni i dokumentirani, što je manje brodove stavilo u nepovoljan položaj kada je u pitanju dodjela kvota.. To je također značilo da su organizacije malog ribarstva onemogućene u sudjelovanju u procesima donošenja odluka na razini EU-a, budući da nije pružena podrška uspostavljanju struktura poput organizacija malih proizvođača.

Ovaj aspekt nedavno je istaknut u posebnom izvješću Europskog revizorskog suda o kontrolama ribarstva EU-a http://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=41459. Time je istaknuto da, kao rezultat primjene pravila Uredbe o kontroli, 89% flote EU-a, od kojih 95% obuhvaća plovila kraća od 12 metara, nije nadziran sustavom za praćenje plovila (VMS). To značajno ometa učinkovito upravljanje ribarstvom u nekim ribolovnim područjima i za neke vrste. U izvješću se također ističe danedostatak transparentnosti u načinu na koji neke organizacije proizvođača upravljaju kvotama povećava rizik da se specifični interesi određenih gospodarskih subjekata favoriziraju na štetu drugih, stvarajući nejednaku konkurenciju među segmentima flote.

U mnogim državama članicama EU-a, aktivnosti malog opsega, tradicionalno polivalentne korištenjem raznih alata tijekom cijele godine, usmjerene su na sezonski raznolik niz vrsta – prava oprema, pravo mjesto, pravo vrijeme – sada je dopušten ulov samo ograničenog raspona vrsta izvan kvote. Tako, na primjer, u Ujedinjenom Kraljevstvu sektor malog ribolova ispod 10 metara, koji brojčano predstavlja 771 TP3T flote, ima pristup samo 1,51 TP3T britanske kvote po tonaži i mora se uglavnom oslanjati na vrste izvan kvote poput morskog puža, smeđeg raka i jastoga. To povećava pritisak na te vrste i obično preplavljuje tržišta, često snižavajući cijene.

U Irskoj, malim ribarima iz otočnih zajednica nije dopušteno loviti ribu u njihovim obalnim vodama. U međuvremenu, superkoćaricama koje love ribu diljem svijeta to je dopušteno, hvatajući vrste koje tradicionalno love i nekažnjeno odvlačeći njihovu opremu. Irski otočani, koje predstavlja Organizacija za morske resurse irskih otoka (IIMRO), predlažu da Irska usvoji sustav “dozvola za baštinu”, dodijeljenih manjim plovilima s fiksnom opremom, u vlasništvu i pod upravom ribara iz otočnih zajednica. Ta bi plovila djelovala u vodama uz otoke, a njima bi se upravljalo prema lokalno vođenom režimu zajedničkog upravljanja.

Financijska potpora je još jedno područje u kojem su velike ribolovne aktivnosti stekle ogromne prednosti na štetu malih aktivnosti. Iako se često kaže da subvencije za industrijski ribolov subvencioniraju prekomjerni izlov, barem u Europi, moglo bi se reći da su u slučaju malog sektora subvencije subvencionirale nedovoljan izlov.

U Europi je u razdoblju od 2000. do 2006. velika većina subvencija za izgradnju i modernizaciju plovila otišla plovilima duljim od 24 metra, dok su plovila kraća od 12 metara primila dvostruko više sredstava za rashodovanje nego za modernizaciju i izgradnju.[2].

Nedavna studija Sveučilišta Britanske Kolumbije izvještava da se na globalnoj razini 841 TP3T subvencija ribarskom sektoru, u vrijednosti od 35 milijardi USD1 TP4T, odnosi na plovila dulja od 24 metra. Ističe se kako subvencije za gorivo potiču tehnologiju koja neučinkovito koristi gorivo i pomažu velikim ribarima da ostanu u poslu, čak i kada operativni troškovi premašuju ukupne prihode ostvarene od ribolova. Subvencije za razvoj luka i izgradnju, obnovu i modernizaciju brodova također daju velikom ribarskom sektoru značajne prednosti u odnosu na male ribarske kolege, koji primaju samo mali postotak tih subvencija. https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-06/uobc-spo053117.php.

Dakle, kako se mogu uspostaviti ravnopravniji uvjeti te transparentniji i pravedniji sustav za dodjelu ribolovnih prava i financijske potpore?

Prije svega, sektor malog ribolova mora biti uključen u regulatornu regulativu. To bi se moglo postići uspostavom diferenciranog pristupa upravljanju aktivnostima malog i velikog ribolova, temeljenog na prostornom upravljanju, s isključivim ribolovnim područjima određenim za fiksne alate malog opsega s malim utjecajem, te ograničavanjem aktivnosti mobilnih alata s većim utjecajem dalje na more.

Prednosti takvog pristupa istaknute su u nedavnom izvješću Škotske federacije ribara košara (SCFF). http://www.scottishcreelfishermensfederation.co.uk/report.htm. SCFF ističe da je kombinacija pristupa “nemiješanja” Marine Scotland i de facto ograničenja ulova košarama koje je nametnuo sektor koćarstva rezultirala time da su koćarice uspjele osigurati 87,71 TP3T ulova škotskih kozica Nephrops; razina pristupa stokovima, prema SCFF-u, nije opravdana ekonomskim ili ekološkim rezultatima sektora koćarstva, ili bilo kojim koherentnim pokazateljem učinka. Ribolov s košarama ne samo da stvara više radnih mjesta po toni ulova, već je i ekonomski učinkovitije (tj. isplativije) uloviti tonu škampa pomoću košara nego koćarenjem po morskom dnu. Preraspodjelom pristupa škampima u korist lova pomoću košara i uspostavljanjem područja isključivo s košarama, Marine Scotland ima priliku povećati ukupnu zaposlenost, ukupne prihode kućanstava, ukupnu dobit/gospodarsku učinkovitost i broj pojedinačnih ribarskih poduzeća u obalnim područjima. Mnoga od tih područja su udaljena i pate od uskog raspona gospodarskih mogućnosti.

Drugo, diferencirani pristup uključivao bi uspostavljanje različiti režimi pristupa za polivalentne operatere malog opsega fiksne opreme s niskim utjecajem s jedne strane i operatere većeg opsega mobilne opreme s druge strane. Prvo bi uključivalo reguliranje pristupa korištenjem kontrola unosa, kao što su dani na moru, prostorna i privremena zatvaranja ribolova te postavljanje ograničenja na količinu opreme koju bilo koje plovilo može koristiti unutar određenog vremenskog okvira. Potonji režim za operatere većeg opsega mogao bi uključivati kombinaciju kontrola unosa (ograničavanje napora, na primjer kroz dane na moru) i kontrola proizvodnje (ograničavanje ulova, na primjer kroz kvote).

The usluga za uslugu To bi značilo da bi se operateri malog ribarskog sektora morali proaktivnije angažirati sa znanstvenicima i upraviteljima ribarstva u pružanju podataka o ulovima ribe koje ostvare koristeći nove tehnologije dostupne zahvaljujući razvoju mobilnih aplikacija za pametne telefone i tablete.

Dostupne su nove, jednostavne i moćne elektroničke tehnologije koje cijeli proces bilježenja podataka na moru čine relativno jednostavnim. http://abalobi.info/, korištenjem pametnih telefona i tableta. Ribari već koriste takve mobilne tehnologije za poboljšanje svojih marketinških aranžmana i učinkovitije sudjelovanje kao pružatelji podataka u upravljanju ribarstvom. Takvi alati za prikupljanje podataka mogli bi se razviti i kao elektronički brodski dnevnici.

Trenutni fokus na plavo gospodarstvo, ciljeve održivog razvoja i klimatske promjene pruža korisnu priliku za razmišljanje o stanju u europskom ribarstvu, isticanje nekih konkretnih činjenica i predlaganje rješenja.

LIFE postoji kako bi pružio predan i specifičan glas prethodno tihoj većini ribara u europskim vodama. LIFE također vjeruje da je potrebna znatno veća transparentnost, pravedniji i ravnopravniji pristup pristupu resursima, neko razlikovanje između mobilnih i pasivnih alata te, što je ključno, znatno poboljšani sustavi zajedničkog upravljanja ribarstvom u obalnim vodama.

Iskorištavanje sinergija i komplementarnosti između malih i velikih flota trebalo bi pružiti mogućnost za stavljanje Europsko ribarstvo na pravednijim i održivijim temeljima za budućnost. To je prilika koju treba iskoristiti i koju svi uključeni ignoriraju na vlastitu odgovornost.

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2014-2019/vella/announcements/press-statement-meidterranean-fisheries-conference-malta_en

[2] http://www.smh.com.au//breaking-news-world/eu-subsidies-have-encouraged-overfishing-study-20100331-re68.html

♦ ♦ ♦

Mjere upravljanja basom za 2017.: preporuke programa LIFE

Brancin: Veliki razlog za zabrinutost

Mjere upravljanja brancinom za 2017.: preporuke LIFE-a, platforme za ribare Europe s niskim utjecajem na prirodu.

Bruxelles, 23. rujna 2016.

Brian O'Riordan

Sastanak u Lilleu u Francuskoj trajao je dva dana, organizacije članice iz Nizozemska, Francuska i Velika Britanija koji predstavljaju male ribare koji ovise o basu, raspravljali su i dogovorili ŽIVOT stajalište za prijenos Europskoj komisiji i državama članicama.

Stanje populacija brancina u Sjevernom moru, La Mancheu i zapadnim vodama stvara stalnu zabrinutost mnogim ribarima, što mnogi smatraju katastrofalnim.

Za neke ključne luke oko Lorienta u južnoj Bretanji, članovi su izvijestili da je ulov ribolova udicom i udicom iznosio samo 20% čak i prije godinu dana, a čak i 60% ovih malih poduzeća ovisnih o Bassu prestalo je s poslovanjem 2016. godine.

S druge strane, ribolov brancina duž južne obale Engleske održao se u nekoliko područja ili se smanjio samo u skladu s ograničenjima uvedenim u posljednje vrijeme.

Usredotočenost na ribarstvo sjeverno od 48.ti Paralelno s tim, bez obzira na lokalnu situaciju, članovi su se složili da se trenutna ograničenja moraju nastaviti zasad, uzimajući u obzir znanstvene savjete i vlastita zapažanja.

Međutim, jasno su stavili do znanja da bilo koji daljnja ograničenja mora biti popraćeno pružanjem hitne financijske pomoći ako se želi da mali ribari prežive dok se razina ribljeg fonda ne poboljša. Izvori Europske komisije obavijestili su ŽIVOT da ako takva odredba već nije uključena u operativne planove EFPR-a država članica, tada bi se ti planovi mogli izmijeniti kako bi je uključili.

Nakon iscrpnih rasprava, članovi su se složili da sljedeći stav za mjere na Bassu sjeverno od 48ti Paralelno:

- Trenutni šestomjesečni moratorij od siječnja do lipnja bit će pomaknut na razdoblje između Studeni i travanj inkluzivno kako bi se osigurala maksimalna zaštita tijekom glavnog razdoblja mriještenja brancina.

- Tamo gdje se uvode dodatna ograničenja za 2017. i nadalje, ona moraju biti popraćenaodgovarajuća financijska naknada kako bi se osiguralo da mali ribari mogu preživjeti dok se zalihe ne poboljšaju. Možda će biti potrebna hitna revizija operativnih planova pojedinih država članica kako bi se osigurala hitna financijska potpora u okviru Europskog fonda za pomorstvo i ribarstvo.

- Trenutni 1% dopušteni usputni ulov za mobilne alate trebao bi ostati na snazi. Predloženom povećanju dopuštenog usputnog ulova na 5% treba se oduprijeti, jer se time potiče ciljani usputni ulov brancina.

- Upravitelji ribarstva trebali bi ozbiljno razmotriti pružanje poticaja svim ribarima izbjegavati Bassa gdje god je to moguće.

- Države članice moraju dati prioritet i poboljšati praćenje, kontrola i provedba svih plovila koja love brancina, bez obzira na to je li riječ o ciljanom ili usputnom ulovu, komercijalnom ili rekreacijskom. To mora uključivati usputne ulove većih koćarica, i pelagičnih i pridnenih, te danske mušičarske brodove koji love brancine u područjima poznate aktivnosti brancina.

- Jačanje praćenja i provedbe od strane država članica u pogledu i za komercijalne i za rekreativne ribare, uključujući poboljšani fokus na edukaciju javnosti vezanu uz marketing ilegalno ulovljenog brancina. Došlo je do jasnog neuspjeha u provedbi prethodnih dodatnih mjera upravljanja od strane država članica, što je važno uključivati značajna kašnjenja tijekom početne faze uvođenja.

- Iako prepoznaje poteškoće svojstvene pokušaju procjene utjecaja trenutnih mjera u kratkoročnom razdoblju, ŽIVOT članovi su pozvali na Komisija istražiti koje informacije i podatke mogu kako bi se jasnije razumjeli ekološki, društveni i ekonomski utjecaji povećane regulacije.

- Povećana zaštita postojećih područja za uzgoj brancina, kako bi se zaštitio pozitivan porast novačenja u posljednjih nekoliko godina od bilo kakvih štetnih aktivnosti. Države članice također bi trebale provesti hitan pregled koji bi vodio do određivanja novih zaštićenih područja gdje je to potrebno. Istovremeno, postoji jasna potreba za poboljšanjem upravljanja i provedbe u tom pogledu jer su trenutne zaštite područja za uzgoj uglavnom neučinkovite.

- Što se tiče ribolova brancina u Biskajskom zaljevu, ŽIVOT Članovi su izjavili da se, uz značajne iznimke, slični trendovi mogu primijetiti i kod onih sjeverno od 48ti paralelno, sa znatno manjim ulovima. Istaknuli su hitnu potrebu za poboljšanim znanstvenim studijama kako bi se osiguralo da upravljanje brancinom tamo ne slijedi isti poguban put koji se uočava sjevernije. Članovi su preporučili potpuni moratorij na ribolov brancina za veljaču i ožujak, za sve ribolovne aktivnosti koje se obavljaju u Biskajskom zaljevu.

- Članovi su na kraju zatražili za sva područja koja dodatna istraživanja, kako bi se bolje razumjela uloga drugih ribolovnih aktivnosti u ometanju mriještenja brancina.

♦ ♦ ♦